Main menu

Common skin conditions

NEWS

Join DermNet PRO

Read more

Quick links

Amelanotic melanoma — extra information

Amelanotic melanoma

Author: Aamenah Al-Ani, Medical Student, University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand. DermNet Editor in Chief: Adjunct A/Prof Amanda Oakley, Dermatologist, Hamilton, New Zealand. January 2018.

Introduction Demographics Causes Clinical features Diagnosis Differential diagnoses Treatment Follow-up Outcome

What is amelanotic melanoma?

Amelanotic melanoma is a form of melanoma in which the malignant cells have little to no pigment. The term 'amelanotic' is often used to indicate lesions that are only partially devoid of pigment while truly amelanotic melanoma where lesions lack all pigment is rare [1].

Nodular melanoma

Ungual melanoma

Amelanotic melanoma 3mm

See more images of amelanotic melanoma

Who gets amelanotic melanoma?

Amelanotic melanoma accounts for approximately 1–8% of all melanomas. The incidence of truly amelanotic melanoma is difficult to estimate, given that many hypopigmented lesions are labelled as amelanotic [1].

Risk factors for developing amelanotic melanoma include:

- Increasing age — although amelanotic melanoma accounts for a significant proportion of melanoma in young children [2]

- Sun-exposed skin — particularly in older people with chronic photodamage.

What causes amelanotic melanoma?

Melanoma is caused by malignant melanocytes. The development of malignancy in melanocytes is due to genetic changes in DNA, but how and why this occurs is largely unknown. The melanoma cells in amelanotic melanoma cannot produce mature melanin granules, which results in lesions that lack pigment.

To account for the lack of pigment, three models have been proposed.

- Amelanotic melanoma may be a poorly differentiated subtype of typical melanoma.

- Amelanotic melanoma may be a de-differentiated melanoma that has lost its normal phenotype.

- Amelanotic melanoma cells may retain their melanocytic identity but gain the ability to form different phenotypes (multipotency) [3].

What are the clinical features of amelanotic melanoma?

Amelanotic melanomas are classically described as 'skin coloured'. A significant proportion is red, pink, or erythematous. Typical early lesions present as asymmetrical macular lesions that may be uniformly pink or red and may have a faint light tan, brown, or grey pigmentation at the periphery. The borders may be well- or ill-defined [4].

Any subtype of melanoma can be amelanotic.

- Nodular melanoma can resemble a skin-coloured or pink melanocytic naevus (mole) or basal cell carcinoma.

- With subungal melanoma, 25% are amelanotic.

- With desmoplastic melanoma, over 50% are amelanotic [5].

- Metastatic melanoma not uncommonly presents with amelanotic lesions even when the primary lesion is pigmented [5].

Amelanotic melanomas may not display the clinical ABCDE criteria (Asymmetry, Border irregularity, Colour variation, large Diameter) that are classically used as melanoma warning signs. Patients and clinicians may not be alert to suspect non-pigmented lesions as melanoma and so amelanotic melanomas are often misdiagnosed. Expanding the ABCD warning signs to include the 3 R’s (Red, Raised, Recent change) may help screen for amelanotic melanoma [6].

How is amelanotic melanoma diagnosed?

Clinical features

Amelanotic melanomas have little to no pigment and can be clinically challenging to diagnose.

A patient’s history of observing a change in a lesion is an important diagnostic factor with amelanotic lesions and amelanotic melanoma should be considered in the differential diagnosis.

Examination of the entire skin surface is also important, as sun damage (eg, actinic keratoses) and other pigmented lesions may provide clinical clues that a non-pigmented or hypopigmented lesion may be an amelanotic melanoma.

Amelanotic superficial spreading melanoma in situ

Amelanotic nodular melanoma

Amelanotic nodular melanoma

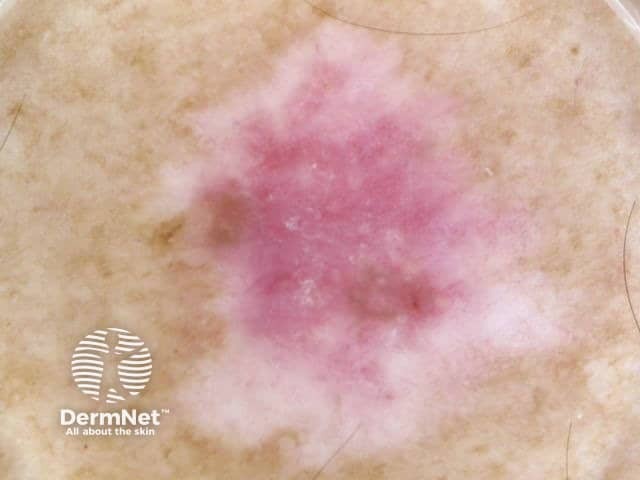

Dermoscopy

Dermoscopy, the examination of a lesion using a dermatoscope, can be helpful in the diagnosis of suspicious lesions. Vessel morphology should be evaluated carefully if lesions are lacking pigmentation.

The characteristic dermoscopic features of amelanotic melanoma are:

- Irregular pigmentation (if any is present)

- Irregular dots or globules (in pigmented areas)

- Polymorphous vascular patterns including milky-red areas, reticular depigmentation, dotted irregular vessels, linear irregular vessels, or the combination of dotted and linear irregular vessels (the most frequent dermoscopic finding)

- White lines [1].

Dermoscopy of melanoma (same lesions as above)

Superficial spreading melanoma in situ

Nodular melanoma

Nodular melanoma

Biopsy

Lesions that are suspicious of amelanotic melanoma should be excised with a 2–3 mm clinical margin and sent for pathological diagnosis (excision biopsy).

Amelanotic melanoma can have varied histopathological appearances. Amelanotic melanoma can masquerade as a number of non-melanocytic neoplasms [7].

- A key feature is the lack of melanin granules; stains that detect melanin granules include Fontana-Masson stain [3].

- Immunohistochemical staining may reveal some residual pigment in amelanotic melanoma and identify the malignant cells as melanocytes.

- Electron microscopy can be used to demonstrate pre-melanosomes in unclear cases.

Pathology report

The pathologist’s report features both a macroscopic and microscopic description of the excised lesion and includes:

- The diagnosis of primary melanoma

- Breslow thickness to the nearest 0.1 mm

- Clark level of invasion

- Margins of excision (the normal tissue around a tumour)

- The mitotic rate (how rapidly the cells are proliferating)

- Whether or not there is any ulceration.

The report may also include comments about the cell type and its growth pattern, invasion of blood vessels or nerves, inflammatory response, regression, immunohistochemistry, and whether there is any associated original benign melanocytic lesion [8].

What is Breslow thickness?

The Breslow thickness is reported for invasive melanomas. It is the vertical measurement in millimetres from the top of the granular layer (or base of superficial ulceration) to the deepest point of tumour involvement. The Breslow thickness is the single most important local prognostic factor in primary melanoma, as thicker melanomas are more likely to metastasise (spread) [8,9].

What is the Clark level of invasion?

The Clark level indicates the anatomic plane of invasion. This is useful for predicting outcome in thin tumours and less useful for thicker ones in comparison to the value of the Breslow thickness [8,9].

What is the differential diagnosis for amelanotic melanoma?

Clinically, amelanotic melanoma may present as an erythematous scaly macule, plaque, or nodule with irregular borders, mimicking numerous other skin lesions such as:

- Basal cell carcinoma

- Spitz naevus

- Seborrhoeic keratosis

- Actinic keratosis

- Pyogenic granuloma

- Dermatofibroma

- Keratoacanthoma

- Intraepidermal squamous cell carcinoma [1,4].

Nodulocystic basal cell carcinoma

Spitz naevus

Pyogenic granuloma

What is the treatment for amelanotic melanoma?

Amelanotic melanoma is treated in the same way that a pigmented melanoma is treated.

After diagnostic excision, the next step is wide local excision of the wound with a 10–20 mm margin of normal tissue. The extent of surgery depends on the Breslow thickness of the melanoma and its site. Amelanotic melanomas may be incompletely excised despite the recommended margins as the margins are often difficult to define. A comprehensive histological examination including immunohistochemical staining helps determine the edge of a tumour. Further re-excision may be necessary. The recommended margins in the provisional 2013 Standards of service provision for melanoma patients in New Zealand are as follows [10]:

- Melanoma in situ (Tis): 5–10 mm

- Melanoma < 1 mm (T1): 10 mm

- Melanoma 1–2 mm (T2): 10–20 mm

- Melanoma 2–4 mm (T3): 20 mm

- Melanoma > 4 mm (T4): 20 mm [9]

Sentinel lymph node biopsy may be discussed with patients with melanomas thicker than 0.8 mm. This can provide staging and prognostic information [9].

Amelanotic melanoma can metastasise (spread to distant sites such as lymph nodes or elsewhere in the body). These cases require individualised treatment that may include surgery, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, or targeted therapy.

What happens at follow-up for amelanotic melanoma?

Follow-up is an important part of the management for amelanotic melanoma because it allows an opportunity to detect recurrences early. It also allows an opportunity to detect new primary melanomas at the earliest opportunity. A second invasive melanoma occurs in 5–10% of patients and an unrelated melanoma in situ affects more than 20% of patients [8].

The 2008 Clinical practice guidelines for the management of melanoma in Australia and New Zealand recommend the following for the follow-up of patients with invasive melanoma:

- Self-skin examinations are performed.

- Regular routine skin checks should be undertaken with the patient’s preferred health professional.

- Follow-up intervals are preferably 6-monthly for 5 years for patients with stage 1 disease, 3-monthly or 4-monthly for 5 years for patients with stage 2 or 3 disease, and yearly thereafter for all patients.

- The individual patient’s needs should be considered before an appropriate follow-up is offered.

- Education and support should be provided to help the patient adjust to their illness [8,9].

What is the outcome for amelanotic melanoma?

The prognosis of amelanotic melanoma is similar to that of pigmented melanomas. Prognostic factors include the Breslow thickness of the melanoma at the time of excision (this is considered to be the most important factor), the location of the lesion, patient age, and sex. Importantly, because of their atypical clinical features, amelanotic melanomas may have a delay in their diagnosis and, consequently, are often more advanced than pigmented melanomas when diagnosed [5].

The risk of metastasis is directly related to the Breslow thickness, with thicker melanomas being more likely to metastasise. The 2008 Clinical practice guidelines for the management of melanoma in Australia and New Zealand report that metastases are rare for thin melanomas (< 0.75 mm), with the risk increasing to 5% for melanomas 0.75–1.00 mm thick. Melanomas thicker than 4.0 mm have a significantly higher risk of metastasis of 40% [9].

References

- Pizzichetta MA, Talamini R, Stanganelli I, et al. Amelanotic/hypomelanotic melanoma: clinical and dermoscopic features. Br J Dermatol. 150: 1117–24. DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2004.05928.x. PubMed

- Stefanaki C, Chardalias L, Soura E, Katsarou A, Stratigos A. Paediatric melanoma. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2017; 31: 1604–15. DOI: 10.1111/jdv.14299. PubMed

- Cheung WL, Patel RR, Leonard A, Firoz B, Meehan SA. Amelanotic melanoma: a detailed morphologic analysis with clinicopathologic correlation of 75 cases. J Cutan Pathol 2012; 39: 33–9. DOI: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.2011.01808.x. PubMed

- Bono A, Maurichi A, Moglia D, et al. Clinical and dermatoscopic diagnosis of early amelanotic melanoma. Melanoma Res 2001; 11: 491–4. PubMed

- Koch SE, Lange JR. Amelanotic melanoma: the great masquerader. J Am Acad Dermatol 2000; 42: 731–4. PubMed

- McClain SB, Mayo KB, Shada AL, Smolkin MA, Patterson JW, Slinguff Jr CL. Amelanotic melanomas presenting as red skin lesions: a diagnostic challenge with potentially lethal consequences. Int J Dermatol 2012; 51: 420–6. DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2011.05066.x. PubMed Central

- Shetty A, Kumar SA, Geethamani V, Rehan M. Amelanotic melanoma masquerading as a superficial small round cell tumor: a diagnostic challenge. Indian J Dermatol 2014; 59(6): 631. DOI: 10.4103/0019-5154.143569. PubMed

- Sladden M, Nieweg O, Howle J, Coventry B; Cancer Council Australia Melanoma Guidelines Working Party. Excision margins for invasive melanoma and melanomas at other sites. Cancer Council Australia Cancer Guidelines Wiki. Available here (accessed 20 September 2017)

- Cancer Council Australia; Australian Cancer Network; New Zealand Ministry of Health. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of melanoma in Australia and New Zealand. Wellington: New Zealand Guidelines Group, 2008.

- National Melanoma Tumour Standards Working Group. Standards of service provision for melanoma patients in New Zealand — Provisional. Wellington: Ministry of Health, 2013.

On DermNet

- Amelanotic melanoma images

- Melanoma pathology

- Melanoma

- Melanoma in situ

- Superficial spreading melanoma

- Lentigo maligna and lentigo maligna melanoma

- Subungal melanoma

- Desmoplastic melanoma

- Spindle cell melanoma

- Nodular melanoma

- Acral lentiginous melanoma

- Metastatic melanoma

- Skin cancer

- ABCDE criteria

Other websites

- Melanoma New Zealand

- Cutaneous melanoma — Medscape

- Melanoma — American Academy of Dermatology

- Melanoma risk assessment tool — Melanoma Institute of Australia

- Melanoma education — Melanoma Institute of Australia