Main menu

Common skin conditions

NEWS

Join DermNet PRO

Read more

Quick links

Phototesting — extra information

Phototesting

Last reviewed: December 2023

Author(s): Dr Hannah Ross, Dermatology Registrar; and Dr Tsui Ling, Consultant Dermatologist, Photobiology Unit, Salford Royal Hospital, Manchester, United Kingdom (2023)

Previous contributors: Dr Amanda Oakley, Dermatologist (1997)

Reviewing dermatologist: Dr Ian Coulson (2023)

Edited by the DermNet content department

Introduction

Photopatch tests

Phototests

Photoprovocation tests

Laboratory investigations

What is phototesting in dermatology?

Phototesting comprises several investigations that are undertaken to determine if a patient has a skin condition caused or aggravated by ultraviolet (UV) exposure.

It can be useful in confirming or excluding photosensitivity, defining the action spectrum of a photosensitive eruption, and diagnosing sunscreen allergies.

Full phototesting consists of:

- Monochromator light testing

- Photoprovocation testing

- Photopatch testing

- Patch testing

- Laboratory investigations.

Not all of the above tests may be indicated for each patient.

Preparation for phototesting

Patients should take care to follow the instructions from their photodermatology clinic, including if/when any medications or topical agents should be discontinued prior to testing. For example, steroid creams and antihistamines are usually stopped at least 48 hours before phototesting, as these can affect results.

Monochromator light testing

Monochromator light testing is an essential aspect of phototesting. The light source used is usually a 2500 watt xenon arc lamp. These lamps have an output that mimics sunlight.

The monochromator is a precision optical device designed to fractionate the light to allow exposure to a clearly defined waveband.

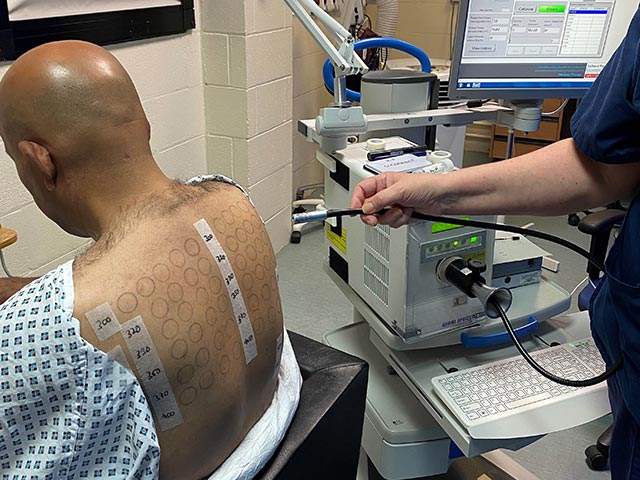

- An area of skin, usually on the patient’s back, is tested to incremental doses of a number of wavelengths.

- Wavelengths tested and dose ranges used vary between different photodermatology units. They may include ultraviolet B (UVB) eg, 300 nm; ultraviolet A (UVA) eg, 320, 330, 350, 370, and 400 nm; and visible wavelengths eg, 500 and 600 nm.

- The skin is then examined 24 hours later to record the minimal erythema dose (MED). The MED is the lowest dose of the wavelength that produces an identifiable pink response.

Undertaking monochromator light testing - differing doses of different wavelenghts of UVB, UVA, and visible light are delivered

Photoprovocation testing

Photoprovocation can induce an eruption in patients with photosensitivity that have normal erythemal thresholds. It can be useful in the diagnosis of various photosensitive disorders including polymorphic light eruption (PMLE), photoaggravated atopic dermatitis, and actinic prurigo.

- Testing is usually performed by exposure to broadband UVA +/- visible optical radiation sources (solar simulator) on a 5x5 cm square on the patient’s forearm.

- Repeated provocation testing increases the yield for a positive response, and the standard protocol should aim for consecutive challenges over a three-day period.

The morphology of the artificially-provoked rash assists in diagnosis. A skin biopsy may be performed (with immunofluorescence if indicated) to further confirm the diagnosis. A negative test may not exclude these conditions.

Ultraviolet radiation provocation testing

Photopatch testing

Photopatch testing aids the diagnosis of suspected contact and/or photocontact sunscreen allergies that may be contributing to photosensitivity. It may also help to guide sunscreen choice for the patient.

As most of the relevant contact allergens are activated by UVA rather than UVB, UVA irradiation is used in photopatch testing. Photopatch test series may include sunscreens, chemical UV filters, and the patient’s own products. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are also commonly tested as they can be implicated in photoallergic reactions.

- Patients have two identical sets of the photocontact allergens applied in parallel to the left and right sides of the back. These are removed after two days.

- One side is then covered with a UV-opaque sheet, while the other side is exposed to 5 J/cm² of UVA. The UVA dose is reduced in patients with significant photosensitivity.

- The patient attends for three consecutive days for reading of the photopatch testing.

A positive photoallergic response is characterised by a positive response on the irradiated series, with a negative response to the same allergen on the non-irradiated side. A positive response on both sides indicates a contact allergy alone. If there is a stronger response on the UV-irradiated side, this would suggest both contact and photocontact allergy.

If multiple sunscreen allergies are evident, it is advisable to refer on for full patch testing to investigate for coexisting contact allergies.

Photocontact testing - two panels of allergens are applied, one set are irradiated with UVA

Laboratory investigations

Laboratory investigations can help formulate a diagnosis in patients with photosensitivity.

Investigations may include:

- Porphyrin screen (blood, urine, faeces)

- Antinuclear antibodies (ANA), anti-SSA (anti-Ro), anti-SSB (anti-La) and/or antibodies to double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) to investigate for autoimmune conditions eg, lupus

- Serum IgE (elevated in photoaggravated eczema and chronic actinic dermatitis)

- Human leukocyte antigen (HLA) genotyping: (HLA-DRB1*04:07 is present in 60% of cases of actinic prurigo)

- Vitamin D status (often low in photoprotected patients).

Side-effects and risks of phototesting

Phototesting is painless, but skin redness and rashes may be induced during the testing process. Contact dermatitis reactions can be itchy.

Diagnosis

Phototesting in isolation seldom provides the diagnosis, except where the tests demonstrate classical solar urticaria or chronic actinic dermatitis.

A diagnosis is often made after correlating symptoms with phototesting findings. However, the diagnosis may not always be certain, due to limitations in patient history, lack of images of skin changes, or equivocal test results.

Following detailed history and examination, phototesting usually concludes the investigations and in most cases is followed by a working diagnosis and management plan.

Patient advice following phototesting

Patient counselling following phototesting includes:

- Verbal explanation about the diagnosis, supported with written information

- Advice on photoprotective measures eg, sun protective clothing, avoidance of midday sun, correct application of sunscreens, and use of UVA-blocking window film

- Information about patient support groups

- A management plan, including suitable sunscreens in photosensitivity disorders where the action spectrum is in the visible-light wavelengths (eg, some solar urticaria, erythropoietic protoporphyria) and a suitable sunscreen is needed (eg, the ‘Dundee’ sunscreen in the UK).

The range and diversity of the photodermatoses mean that counselling requirements differ. For example, with PMLE a simple explanation of the disorder and its management may suffice. For chronic actinic dermatitis, a more detailed explanation is usually required, particularly in older patients, who may find it challenging to accept the nature of the condition and the need for meticulous photoprotection.

In children with photodermatoses, the counselling is given to the parents, usually with the child in attendance. For severe congenital photosensitivity syndromes such as xeroderma pigmentosum or congenital erythropoietic protoporphyria, this is best managed by a multidisciplinary team. This ensures sufficient expertise to provide the family with a clear understanding of the disorder and its implications, the management plan, and the prognosis.

Some patients may initially be unaccepting of their diagnosis, and appropriate support and encouragement may be needed.

Further appointments may be needed with the referring doctor or the photodermatology clinic if diagnosis or management is not straightforward.

Bibliography

- Ibbotson S. How should we diagnose and manage photosensitivity? J R Coll Physicians Edinb. 2014;44(4):308–12. doi: 10.4997/JRCPE.2014.413. PDF

- Ling TC, Ayer J. Photosensitivity. In: Chowdhury MMU, Griffiths TW, Finlay AY, eds. Dermatology Training: The Essentials. Wiley Blackwell; 2022:336–9.

On DermNet

- Photosensitivity

- Photocontact dermatitis

- Patch tests

- Ultraviolet radiation and human health

- Sun protection

- Sun protective clothing

- Sunscreens

- Sunscreen allergy

Other websites

- Phototesting: Patient information factsheet (PDF) — NHS University Hospital Southampton, NHS Foundation Trust

- Photopatch testing: Patient information factsheet (PDF) — NHS University Hospital Southampton, NHS Foundation Trust