Main menu

Common skin conditions

NEWS

Join DermNet PRO

Read more

Quick links

Fragrance allergy — extra information

Fragrance allergy

Author: Elaine Luther, Medical Student, Ross University School of Medicine, Barbados, West Indies. Medical Editor: Dr Helen Gordon, Auckland, New Zealand. DermNet Editor in Chief, Adjunct A/Prof Amanda Oakley, Dermatologist, Hamilton, New Zealand. Copy edited by Gus Mitchell. July 2020.

Introduction

Demographics

Causes

Clinical features

Diagnosis

Limits

Other tests

Differential diagnoses

Treatment

Outcome

Appendix: list of 26 fragrances requiring labelling in the EU

What is a fragrance allergy?

Fragrance allergy is an allergic contact dermatitis to a fragrance chemical.

Fragrances and perfumes can either be made from a natural extract or synthesised. They produce a pleasant scent or disguise the unpleasant odour of a product.

Allergy requires prior sensitisation to the fragrance chemical. Subsequent skin contact with the chemical causes a delayed hypersensitivity reaction (type IV) in the hours to days after exposure.

Who gets a fragrance allergy?

Fragrance allergy is common and is believed to affect around 1% of adults [1]. Rates in children and adolescents are around 1.8%. Fragrance allergy is second only to nickel allergy as a cause of allergic contact dermatitis. However the frequency of relevant positive reactions in dermatology departments is falling due to the reduced use of oakmoss absolute as a fragrance.

Allergic contact dermatitis occurs as frequently in people with and without a history of atopic dermatitis.

Fragrances are not limited to perfumes and cosmetics. They are also found in:

- Personal care products such as body wash, lotions, shampoos, conditioners, deodorants, baby wipes, and sanitary pads

- Household products such as laundry detergents, fabric softener, air freshener, cleaning agents, candles, pot pourri, and toilet paper

- Flavours added to food and drinks, lipsticks, lip balms, and toothpaste.

- Work place chemicals may also have aromas added to cover unpleasant smells, for example coolant oils, histology solvents, industrial solvents.

- Occupational dermatitis due to fragrance allergy is seen in hairdressers, in chefs and bakers due to flavouring agents and citrus fruit, and in aromatherapists and masseurs due to use of scented natural oils.

- Topical medicaments and balms.

- Electronic cigarettes.

Anyone who uses or is exposed to fragranced products can become sensitised to them over time. Consort allergy is well-recognised.

What causes fragrance allergy?

A European Scientific Committee on Consumer Safety review of fragrances in 2011 listed 82 substances that had been established as contact allergens including 54 synthetic chemicals and 28 natural extracts. Twelve of the chemicals and 8 of the natural extracts were listed as being at high risk of causing sensitisation.

Among the most common are the 15 fragrances that can be identified by patch testing with balsam of Peru, Fragrance Mix I (FM I), and Fragrance Mix II (FM II). Isoeugenol is the most common positive allergen in Fragrance Mix I, and hydroxyisohexyl 3‑cyclohexene carboxaldehyde (Lyral) in Fragrance Mix II.

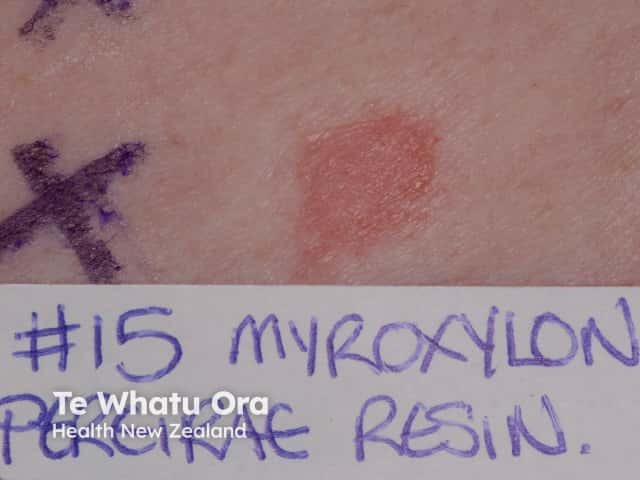

Positive patch test to fragrance - balsam of Peru

Positive patch test to fragrance - fragrance mix I

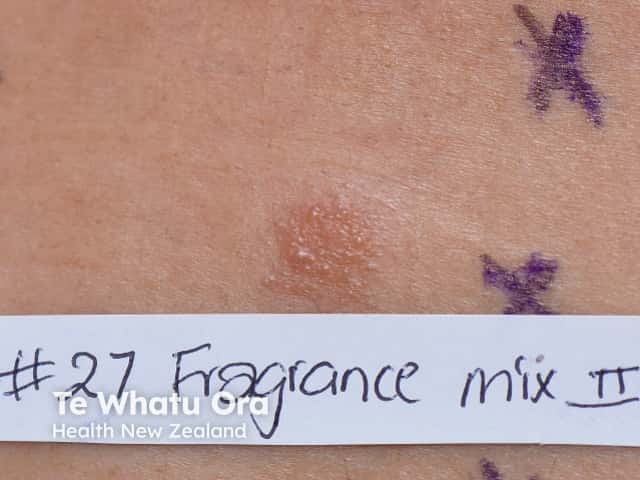

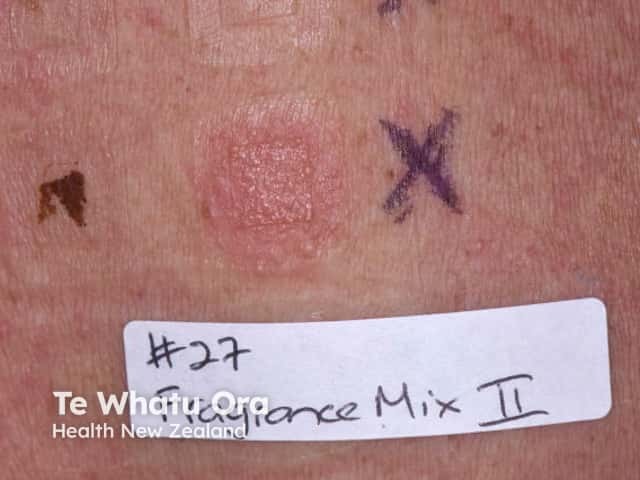

Positive patch test to fragrance - fragrance mix II

What are the clinical features of fragrance allergy?

Fragrance allergy presents as a dermatitis which is often in a streaky pattern where there has been direct contact with the fragrance allergen.

- In women, the hands, face, and neck are most commonly affected.

- In men, the hands, face, and lower legs are most often affected.

- The fragrance chemical can be transferred to an unexpected site, for example, via the hands onto the face.

- Involvement of the armpits is common in both sexes.

- Other locations affected include perianal skin if perfumed toilet paper wet wipes, or haemorrhoid preparations are used.

Typically, fragrance allergy presents as scaly erythematous plaques.

- There can be swelling, vesicles, and bullae.

- Continued exposure to the allergen may result in chronic dermatitis with lichenification and excoriation.

- The dermatitis is itchy and may also burn and sting.

- Dermatitis can be complicated by a secondary bacterial infection.

Fragrance allergy may affect the mouth (allergic contact stomatitis) resulting in cheilitis, gingivitis, blisters and erosions, or oral lichen planus.

Photoallergy to fragrances has become less common in those countries where the use of musk ambrette has reduced.

Contact allergy on axilla

Contact allergy on neck

Contact allergy on hand

How is fragrance allergy diagnosed?

A diagnosis of fragrance allergy will typically require a detailed patient history and is confirmed by patch testing.

- Around 10% of those undergoing patch testing are found to have a fragrance allergy.

- The relevance of a positive patch test should be determined by the distribution of the rash and the products used.

- A weakly positive patch test can be due to irritation by the fragrance chemical rather than a true contact allergy.

Fragrance mix II +

Fragrance mix II ++

Fragrance mix II +++

Which allergens test for fragrance allergy?

Patch testing for fragrance allergies usually begins with a baseline series of allergens. These should include balsam of Peru, Fragrance Mix I, and Fragrance Mix II.

Balsam of Peru is extracted from the Myroxylon pereirae tree. It cross-reacts with other fragrances and a positive reaction occurs in around 50% of patients with fragrance allergy.

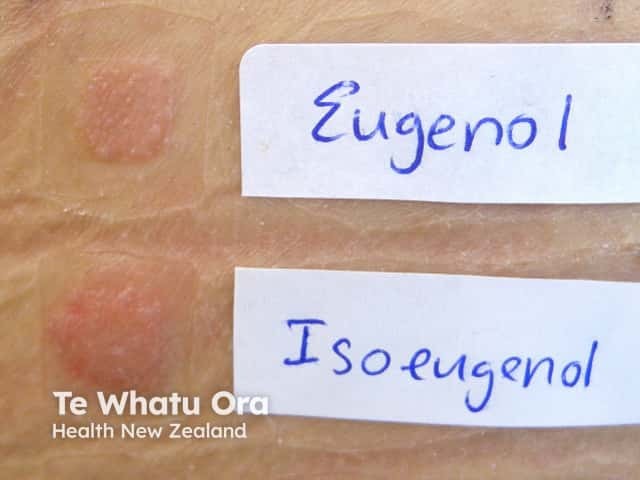

Fragrance Mix I can identify 75% of those with fragrance allergy when combined with balsam of Peru. It is a mixture of eight fragrances:

- Oakmoss absolute

- Isoeugenol

- Eugenol

- Cinnamyl alcohol

- Cinnamaldehyde

- Hydroxycitronellol

- Geraniol

- Amyl cinnamaldehyde.

Fragrance Mix II increases the sensitivity of testing as it is a mixture of a further six fragrances:

- Lyral

- Citral

- Farnesol

- Coumarin

- Citronellal

- Alpha-hexyl cinnamaldehyde.

Eugenol/isoeugenol

Lyral

Multiple fragrance reactions

The fragrance series

A patient identified as having a fragrance allergy can be tested with the 26 individual fragrances that require labelling in the European Union. A patient with a positive patch test result to one of the members of the fragrance series can avoid that fragrance by reading labels. See Appendix at the end.

What are the limits of patch testing?

Even if a specific fragrance chemical is identified as causing allergy, it can be difficult to avoid every product that contains it.

- Manufacturers may not list any or all of their ingredients.

- Ingredients can be changed without giving notice to consumers.

- The allergen may be present in low concentration, and ingredients must only be listed in a regulated product if they surpass a specified threshold concentration.

It can be futile to test for fragrances that are never labelled since the patient will not be able to identify which products contain the fragrance they have reacted to.

What other tests can be done?

Any leave-on product the patient suspects is causing an allergy can be applied as a customised patch for testing. Patch testing is not suitable for undiluted wash-off products as they are often irritate if left on the skin.

The ‘repeat open application test’ is often more practical and cost-effective than patch testing. Before using a new fragrant leave-on product, the patient applies a dot of the product to the same area of the forearm or inner upper arm twice a day for two weeks. If a rash develops, the product should not be used.

What is the differential diagnosis for fragrance allergy?

The differential diagnosis for fragrance allergy may include:

- Allergic contact dermatitis from another allergen

- Irritant contact dermatitis

- Atopic eczema

- Contact urticaria.

What is the treatment for fragrance allergy?

Treatment of fragrance allergy requires identification of the allergen followed by avoidance if possible. Treating the allergic contact dermatitis that results from exposure to a fragrance allergen may include:

- A topical steroid appropriate for the severity and body site

- A short tapering course of systemic steroid (eg, prednisone)

- Regular use of emollients.

What is the outcome for fragrance allergy?

Fragrances are ubiquitous and avoidance can be a challenge.

- The sensitive person can be allergic to several fragrances.

- Identifying every product that contains the fragrance is virtually impossible — ingredients may not listed and often have multiple names; for example, balsam of Peru has 13 names according to the Contact Dermatitis Institute.

The fragrance-allergic patient is best to avoid products that are unlabelled or contain any fragrance.

Select products labelled ‘fragrance-free’ (so-called ‘unscented’ products) but these could still include masking fragrances. Products may contain an unidentified fragrance, for example, if they list ‘botanical’, ‘herbal’, or ‘natural’ ingredients.

The fragrance-allergic patient can use the open application test to screen any new products.

APPENDIX: 26 Fragrances that require labelling in the European Union

The 26 fragrances in the fragrance series are:

- Amyl cinnamal

- Cinnamal

- Cinnamyl alcohol

- Eugenol

- Geraniol

- Hydroxycitronellal

- Isoeugenol

- Citral

- Citronellal

- Coumarin

- Farnesol

- Alpha-hexyl innamal

- Hydroxyisohexyl 3-cyclohexene carboxaldehyde (Lyral)

- Alpha-amycinnamyl alcohol

- Anise alcohol

- Benzyl alcohol

- Benzyl benzoate

- Benzyl cinnamate

- Benzyl salicylate

- Limonene

- Butylphenyl methylpropional

- Linalool

- Methyl 2-octynoate

- Alpha isomethylionone

- Evernia furfuracea (tree moss extract)

- Evernia prunastri (oakmoss extract).

References

- Wilkinson M, Orton D. Allergic contact dermatitis. In: Griffiths C, Barker J, Bleiker T, Chalmers R, Creamer D (eds). Rook's Textbook of Dermatology 9th edn. Wiley Blackwell 2016: 128.25-7.

- Storrs FJ. Fragrance. Dermatitis. 2007;18:3–7. doi: 10.2310/6620.2007.06053. PubMed

- Fragrance allergy. In: Reitschel E and Fowler JF. Fisher’s Contact Dermatitis. Sixth edition. BC Decker Inc 2008, pp 393–404.

- Hamann CR, Hamann D, Egeberg A, Johansen JD, Silverberg J, Thyssen JP. Association between atopic dermatitis and contact sensitization: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:70–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2017.02.001. PubMed

- Heisterberg MV, Andersen KE, Avnstorp C, et al. Fragrance mix II in the baseline series contributes significantly to detection of fragrance allergy. Contact Dermatitis. 2010,63:270–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.2010.01737.x. Journal

- Ung C, White J, White I, Banerjee P, McFadden J. Patch testing with the European baseline series fragrance markers: a 2016 update. Br J Dermatol. 2018;178:776–80. doi: 10.1111/bjd.15949. PubMed

- Edwards A, Blickenstaff N, Coman, G, Maibach H. Dermatotoxicologic clinical solutions: clinical management of fragrance mix #1 #2 patients? Cutan Ocul Toxicol. 2015;34:167–70. doi: 10.3109/15569527.2014.926368. Journal

- Uter W, Werfel T, Lepoittevin JP, White IR. Contact allergy-emerging allergens and public health impact. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(7):2404. doi:10.3390/ijerph17072404. Journal

On DermNet

- Balsam of Peru allergy

- Baseline series of patch test allergens

- Cosmetics allergy

- Consort allergic contact dermatitis

- Fragrance mix allergy

- Fragrances and perfumes

- Open application test

- Patch tests

Other websites

- Allergy New Zealand

- Allergic contact dermatitis — Medscape

- Allergen of the year — Medscape

- Fragrance — American Contact Dermatitis Society

- Allergen information — Contact Dermatitis Institute