Main menu

Common skin conditions

NEWS

Join DermNet PRO

Read more

Quick links

Tinea capitis — extra information

Tinea capitis

Page created 2003. Adjunct A/Prof. Amanda Oakley, Dermatologist, Hamilton, New Zealand. Updated: Dr Harriet Bell, House Officer, Middlemore Hospital, Auckland, New Zealand. Copy edited by Gus Mitchell. September 2020.

Introduction

Demographics

Causes

Spread

Occurrence

Clinical features

Complications

Diagnosis

Differential diagnoses

Treatment

Outcome

What is tinea capitis?

Tinea capitis is a fungal infection of the scalp, involving both the skin and hair. It is also known as scalp ringworm. Symptoms of tinea capitis include hair loss, dry scaly areas, redness, and itch. Tinea barbae is essentially the same condition involving the beard area.

Tinea Capitis

Tinea Capitis

Tinea Capitis

Who gets tinea capitis?

Tinea capitis predominantly affects preadolescent children, with incidence peaking between the ages of three and seven years. It can also affect adults, particularly those who are immunocompromised. Tinea capitis is found in most parts of the world, although the prevalence of a particular fungal species causing tinea capitis varies geographically. Risk factors include animal contact, household crowding, lower socioeconomic status, warm humid environments, and contact sport. The introduction of antifungal agents, population movements, and improved hygiene practices are associated with evolving patterns of infection.

What causes tinea capitis?

Tinea capitis is caused by dermatophytic fungi capable of invading keratinised tissue, such as the hair and nails. While over 40 different species of dermatophytes are known to exist, only a small number are associated with tinea capitis. Dermatophytes may be classified into three broad categories, according to host preference: anthropophilic species (humans), zoophilic species (animals), and geophilic species (soil).

In New Zealand, Europe, and Asia the most common causative agent is the zoophilic species Microsporum canis which originates in cats.

Examples of other zoophilic fungi that cause tinea capitis include:

- M. nanum (host — pigs)

- M. distortum (variant of M. canis)

- T. equinium (host — horses)

- T. verrucosum (host — cattle).

Trichophyton tonsurans is an anthropophilic dermatophyte that is the most common cause of tinea capitis in the United States. T. violaceum is an anthropophilic fungus seen in New Zealand in patients who have migrated from Africa or the Middle East.

Examples of other anthropophilic fungi that cause tinea capitis include:

- T. soudanese

- T. schoenleinii

- T. rubrum

- M. audouinii.

Geophilic fungi, such as M. gypseum, originate in the soil and are rare causes of tinea capitis.

How is tinea capitis spread?

Tinea capitis is a contagious infection. Anthropophilic species are spread following contact with infected persons, including asymptomatic carriers, or contaminated objects (fomites). Fomites that can harbour anthropophilic dermatophytes include hairbrushes, hats, towels, bedding, couches, and toys; fungal spores may remain viable on these for months. Zoophilic species are transmitted from infected animals, including household pets (especially kittens) or stray cats and dogs. Zoophilic species can spread person-to-person.

How does tinea capitis infection occur?

Following invasion of the keratinised stratum corneum of the scalp (see structure of the normal skin), the fungus grows downwards into the hair follicle and the hair shaft. It penetrates the hair cuticle and typically invades the hair shaft in one of three ways:

- Ectothrix infection: the dermatophyte grows within the hair follicle and covers the surface of the hair. Fungal spores are evident on the outside of the hair shaft and the cuticle is destroyed. M. canis is an ectothrix dermatophyte.

- Endothrix infection: the dermatophyte invades the hair shaft and grows within it. Fungal spores are retained inside the hair shaft, and the cuticle is not destroyed. T. tonsurans is an endothrix dermatophyte.

- Favus infection: a chronic dermatophyte infection caused by T. schoenleinii and characterised by clusters of hyphae at the base of the hairs, with air spaces in the hair shafts. Clinically there is yellow crusting around the hair shaft.

What are the clinical features of tinea capitis?

Clinical features vary according to the species of dermatophyte, type of hair invasion, and the extent of the inflammatory host response. In all types, partial hair loss with some degree of inflammation is characteristic.

The clinical features may be broadly categorised into non-inflammatory and inflammatory variants.

Non-inflammatory variants

Non-inflammatory variants of tinea capitis infection include the following.

- Grey patch: fine scaling of the scalp and patches of alopecia, which appear grey due to spores coating the affected hairs. Variable erythema may be observed; this is usually minimal with anthropophilic species but may be marked with zoophilic or geophilic species.

- Black dot: fine scaling with patches of alopecia, which appear speckled with black dots. The “dots” are broken hair shafts secondary to endothrix infection.

- Diffuse scale: resembles generalised dandruff; alopecia is subtle or absent.

Inflammatory

Inflammatory variants of tinea capitis infection include the following.

- Diffuse pustular: patchy alopecia with associated pustules or folliculitis. Secondary infection with bacteria or other fungi may occur.

- Kerion: a severe inflammatory reaction, resulting from a delayed immune response to the fungus. This pattern progresses to form a painful, erythematous, boggy plaque, with associated alopecia and scattered pustules. It is usually caused by a zoophilic species and may result in permanent alopecia.

- Favus: a rare chronic inflammatory infection caused by T. schoenleinii. It is characterised by matted hair and formation of yellow, crusted cup-shaped lesions (scutula) around the base of the hairs. Scutula contain hyphae and keratin debris, and may coalesce to form a large mass.

The fungal infection may extend to involve other hair-bearing sites including eyebrows and eyelashes, and regional lymphadenopathy may be present.

Clinical types of tinea capitis

Grey patch scalp ringworm

Black dot scalp ringworm

What are the complications of tinea capitis?

Alopecia can result in psychosocial distress for the patient, especially when scarring alopecia following inflammatory tinea capitis results in permanent bald patches. A secondary rash may occur with inflammatory tinea capitis, particularly after initiating antifungal treatment; this is known as a dermatophytide or id reaction. Rarely, erythema nodosum has been known to occur. Secondary bacterial infection may develop.

How is tinea capitis diagnosed?

Tinea capitis is usually suspected clinically but should be confirmed on microscopy and culture (see laboratory tests for fungal infections).

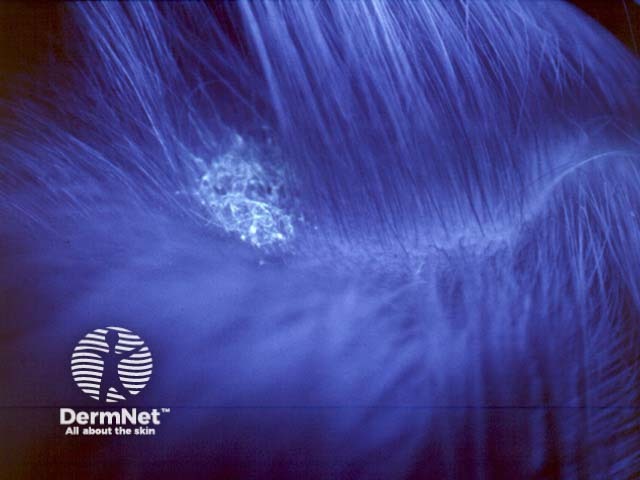

Wood lamp

Wood lamp examination is diagnostic when hair fluorescence is seen, although few fungi cause infected hairs to fluoresce. Bright green fluorescence of infected hairs is observed in tinea capitis caused by Microsporum species (M. ferruginium, audouinii, canis, and distorum). Identifying affected hairs in this way may help with obtaining an appropriate specimen for microscopy and culture. Wood lamp examination is of no value in nonfluorescent endothrix Trichophyton infection, with the exception of T. schoenleinii, which can fluoresce a dull grey-green.

Tinea capitis: Wood lamp fluorescence

Tinea capitis

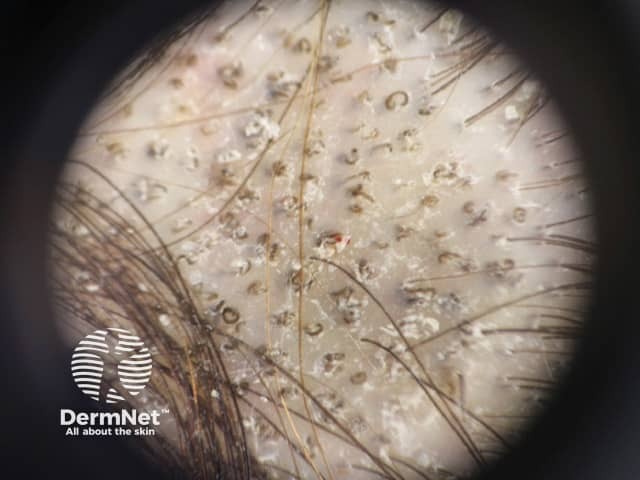

Dermoscopy and trichoscopy

Dermoscopy of the scalp (trichoscopy) is a fast and non-invasive procedure useful for confirming tinea capitis so that treatment can be started while waiting for culture results.

Dermoscopic findings characteristic of tinea capitis with a high predictive value but not seen in every case include:

- Comma hairs (short hairs that bend and grow back toward the scalp, resembling a comma)

- Corkscrew hairs (short hairs that are coiled up like a corkscrew)

- Zigzag hairs (short hairs with several bends in them like a zigzag pattern)

- Barcode-like (Morse code-like) hairs

- Bent hairs.

Corkscrew hairs are typical of Trichophyton infection and are seen less commonly in infection due to M. canis.

Signs seen commonly on dermoscopy of tinea capitis, but which are not diagnostic include:

- Scale, follicular keratosis, and crusts

- Erythema

- Broken hairs

- Black dots.

Dermoscopy of tinea capitis

Microscopy

Microscopy of scalp scrapings or plucked hairs can rapidly confirm the diagnosis of tinea capitis. Specimens are wet-mounted in potassium hydroxide and examined under a light microscope for the presence of hyphae and spores.

Culture

Fungal culture allows identification of the causative agent, and hence the possible source of infection. However, it is slow, taking up to 4 weeks, and treatment is usually required before the result is available.

Endothrix and ectothrix microscopy

Ectothrix invasion by fungal hyphae in a hair shaft

Endothrix invasion of a hair shaft by Trichophyton tonsurans

Molecular diagnostic techniques

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) screening may result in faster and more sensitive ways of detecting dermatophyte infection, but is not yet widely available.

Scalp biopsy

Sometimes the diagnosis of tinea capitis is made on skin biopsy when characteristic changes are seen (see tinea capitis pathology).

What is the differential diagnosis for tinea capitis?

The differential diagnosis list is extensive and includes any condition which may present with patchy alopecia, inflammation, or scaling of the scalp. Examples include:

- Alopecia areata and trichotillomania; cause patchy alopecia but are not scaly

- Seborrhoeic dermatitis, atopic dermatitis, and scalp psoriasis; may mimic non-inflammatory tinea capitis, but the scale is usually more diffuse

- Discoid lupus erythematosus and lichen planopilaris; cause scarring alopecia

- Bacterial scalp folliculitis, impetigo, pyoderma, and pyogenic abscess; may resemble inflammatory tinea capitis.

What is the treatment for tinea capitis?

Tinea capitis always requires at least 4 weeks of systemic medication, as topical agents cannot penetrate the root of the hair follicle. Griseofulvin has previously been the most widely used medication to treat tinea capitis, but it is no longer available in some countries, including New Zealand. Newer antifungal agents such as terbinafine, itraconazole, and fluconazole are at least as effective as griseofulvin for trichophyton infections but less effective for microsporum species.

Topical agents such as povidone-iodine, ketoconazole, and selenium sulfide shampoos can be used to reduce spore transmission.

All members of the household should be screened for tinea capitis and treated simultaneously if found to be affected. Sharing of potential fomites such as hairbrushes, hats, and pillows should be discouraged, and these should be properly cleaned.

In cases of zoophilic infection, family pets should be checked by a veterinarian and treated accordingly.

What is the outcome for tinea capitis?

Non-inflammatory tinea capitis carries an excellent prognosis with appropriate and early treatment. Severe inflammatory tinea capitis may result in areas of permanent alopecia.

Bibliography

- Chen X, Jiang X, Yang M, et al. Systemic antifungal therapy for tinea capitis in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;(5):CD004685. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004685.pub3. PubMed

- Fuller LC, Barton RC, Mohd Mustapa MF, Proudfoot LE, Punjabi SP, Higgins EM. British Association of Dermatologists' guidelines for the management of tinea capitis 2014. Br J Dermatol. 2014;171(3):454–63. doi:10.1111/bjd.13196. PubMed

- Leung AKC, Hon KL, Leong KF, Barankin B, Lam JM. Tinea capitis: an updated review. Recent Pat Inflamm Allergy Drug Discov. 2020;14(1):58–68. doi:10.2174/1872213X14666200106145624. PubMed

- Khosravi AR, Shokri H, Vahedi G. Factors in etiology and predisposition of adult tinea capitis and review of published literature. Mycopathologia. 2016;181(5-6):371–8. doi:10.1007/s11046-016-0004-9. PubMed

- Zhan P, Liu W. The changing face of dermatophytic infections worldwide. Mycopathologia. 2017;182(1-2):77–86. doi:10.1007/s11046-016-0082-8. PubMed

- Singh D, Patel DC, Rogers K, Wood N, Riley D, Morris AJ. Epidemiology of dermatophyte infection in Auckland, New Zealand. Australas J Dermatol. 2003;44(4):263–6. doi:10.1046/j.1440-0960.2003.00005.x. PubMed

- Hay RJ. Tinea capitis: current status. Mycopathologia. 2017;182(1-2):87–93. doi:10.1007/s11046-016-0058-8. PubMed Central

- Waśkiel-Burnat A, Rakowska A, Sikora M, Ciechanowicz P, Olszewska M, Rudnicka L. Trichoscopy of tinea capitis: a systematic review. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2020;10(1):43–52. doi:10.1007/s13555-019-00350-1. PubMed

On DermNet

- Tinea

- Trichoscopy of localised noncicatricial hair loss

- Introduction to fungal infections

- Mycology of dermatophyte infections

- Laboratory tests for fungal infection

- Kerion

Other websites

- Fungal infections of the skin — DermNet e-lecture [Youtube]

- Tinea capitis — Medscape Reference

- Ringworm on Scalp — emedicinehealth

- Tinea capitis — British Association of Dermatologists

- Management of Tinea Capitis — International Foundation for Dermatology