Main menu

Common skin conditions

NEWS

Join DermNet PRO

Read more

Quick links

Inflammatory skin diseases

Created 2008.

Learning objectives

- Define common terms used in dermatopathology of inflammatory skin diseases

- Describe the pathological features of common inflammatory skin diseases

- Describe potential errors in dermatopathological diagnosis

Introduction

Pathological changes may arise in epidermis, dermis and/or subcutaneous tissue. The pattern of changes may allow a diagnosis to be made or it may be non-specific. The appearance of many skin diseases vary at different stages of their development and may be altered by attempted treatment and secondary changes such as scratching or infection.

Understanding the terminology used in describing pathological changes in the skin will help interpret pathology reports. The reporting pathologist will generally make or suggest a diagnosis or possible diagnoses, but it is especially important in inflammatory conditions that the report be correlated with the clinical features. If the clinical and pathological diagnoses do not tally, the case should be discussed with the pathologist to arrive at a consensus diagnosis (or to at least agree that a definite diagnosis is not possible at this stage).

The pathology of the following skin diseases will be outlined.

- Eczema

- Psoriasis

- Lichen planus

- Bullous pemphigoid

- Vasculitis

- Granuloma annulare

- Acne

Terminology in dermatopathology

Descriptions refer to routine sections stained with haematoxylin and eosin (H&E).

Epidermal changes

| Hyperplasia | Increase in the number of cells |

| Hyperkeratosis | Thickening of the stratum corneum |

| Orthokeratosis | Hyperkeratosis without parakeratosis |

| Parakeratosis | Flattened keratinocyte nuclei within the stratum corneum |

| Follicular plugging | Hyperkeratosis within hair follicle |

| Hypergranulosis | Thickened granular layer (may have associated hyperkeratosis) |

| Hypogranulosis | Decreased thickness of granular layer (may have associated parakeratosis) |

| Acanthosis | Thickened squamous cell layer |

| Psoriasiform hyperplasia | Regular acanthosis, with elongation of rete ridges, as seen in chronic plaque psoriasis |

| Papillomatosis | Elevation of adjacent dermal papillae above the surrounding epidermal surface |

| Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia | Extensive acanthosis simulating well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma |

| Epidermal atrophy | Decreased thickness of epidermis |

| Cellular vacuolisation | Intracellular clear rounded spaces |

| Spongiosis | Intercellular oedema between keratinocytes (sometimes associated with exocytosis) |

| Exocytosis | Inflammatory cells within epidermis (usually refers to lymphocytes, and implies a benign process) |

| Acantholysis | Separation and rounding up of keratinocytes because of loss of intercellular adhesions |

| Dyskeratosis | Abnormally or prematurely keratinised eosinophilic keratinocytes, identified by prominent eosinophilic (red-staining) cytoplasm |

| Colloid bodies | Non-nucleated eosinophilic deposits in lower epidermis or upper dermis formed from the intracellular filaments of dead keratinocytes, and may entrap immunoglobulin or fibrin |

| Corps ronds and grains | Acantholytic dyskeratotic cells |

| Apoptosis | ‘Programmed cell death’ of individual cells. Produces colloid bodies (which initially may contain shrunken dark nuclei). |

| Vacuolar degeneration | Damage to the basal layer, with intracellular oedema and vacuoles. May be associated with colloid body formation and clear spaces at the dermal-epidermal junction, sometimes resulting in a subepidermal blister. |

Spongiosis Spongiosis Parakeratosis Parakeratosis

Dermal changes

| Melanin incontinence | Melanin in the upper dermis following damage to basal cells |

| Dermal atrophy | Decreased thickness of the dermis |

| Oedema | Accumulation of interstitial fluid (may be difficult to identify and can have a similar appearance to mucin) |

| Hyalinisation | Accumulation of dense ‘hard looking’ eosinophilic acellular material (stains red/pink) |

| Solar elastosis | Accumulation of basophilic material (grey/blue) in the upper dermis of photo-aged skin |

| Sclerosis | Hyalinised collagen with decreased fibroblasts |

| Mucin | Pale blue threadlike or granular staining. Larger amounts ‘myxomatous’ (washed-out), resemble oedema |

| Calcification | Dark blue brittle deposits: Metastatic – may involve blood vessels; Dystrophic – affects damaged tissue |

| Haemosiderin | Brown iron-containing pigment from disintegrated red blood cells. Must be differentiated from melanin. |

| Cleft | Empty space that previously contained material that has been dissolved in tissue processing such as fluid, crystals or lipid |

Cells

| Neutrophils | Often referred to as ‘polymorphs’. Hypersegmented nuclei; cells clustered into abscesses or scattered in the epidermis. In large numbers in the dermis in infections and ‘neutrophilic’ dermatoses such as Sweet syndrome, pyoderma gangrenosum, and hidradenitis suppurativa. |

| Eosinophils | Segmented nuclei. Obvious numerous red (eosinophilic) granules in the cytoplasm. Associated with bullous disease (especially bullous pemphigoid), eosinophilic cellulitis, hypereosinophilic syndrome, eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis, allergies, drug reactions, parasitic infestation, and insect bites, but is not specific. May be found in the epidermis or dermis. |

| Neutrophils and Eosinophils | Examples are drug eruption, chronic spontaneous urticaria, urticarial vasculitis, granuloma faciale, and Schnitzler syndrome |

| Plasma cells | Clock face nuclei, paranuclear clearing. Characteristic of chronic inflammation near mucous membranes and often seen around invasive tumours. |

| Lymphocytes and histiocytes | The predominant cell type in most inflammatory skin diseases. Histiocytes are macrophages, and may be seen to have engulfed debris. Lymphocytes are characteristically observed in a viral exanthem, pigmented purpura, gyrate erythema, polymorphous light eruption, lupus tumidus, and cutaneous lymphoid hyperplasia. |

| Multinucleated giant cells | Large cells containing multiple nuclei, which are usually formed from histiocytes, but there are several different types, which may suggest particular infections or tumours. |

| Granulomas | Nodular aggregate of histiocytes and other inflammatory cells. There are several subtypes, which may suggest specific infectious or non-infectious causes. |

| Red cells | Extravasated into epidermis (rare) or dermis |

| Mast cells | Classically have a ‘fried-egg’ appearance, but may be spindle or stellate shaped and very hard to identify without special stains. |

Common patterns

There are two main schools of thought as to how inflammatory dermatoses should be described, but both are essentially a means to categorise changes into recognisable overall broad tissue reaction patterns, and then home in on more subtle changes to arrive at a diagnosis. One is based largely around the epidermal changes (spongiotic, lichenoid, psoriasiform or bullous), while the other identifies the basic pattern of inflammatory cell infiltration (superficial perivascular, superficial and deep perivascular, diffuse dermatitis, nodular dermatitis, and vesicular). Both systems have their merits, and many dermatopathologists use a combination of both.

| Perivascular dermatitis | Inflammatory cells are clustered around blood vessels. In superficial perivascular dermatitis the deeper dermal vessels are unaffected; in superficial and deep, all are affected. |

| Lichenoid dermatitis | An infiltrate of lymphocytes affects and obscures the basal epidermis, classically with a band like pattern. Sometimes the infiltrate is patchy. There is associated basal cell degeneration. |

| Spongiotic dermatitis | Typical of eczema, the epidermis shows patchy spongiosis, nearly always with associated exocytosis of lymphocytes. |

| Diffuse dermatitis | A dense dermal infiltrate of mixed inflammatory cells which does not form obvious discrete nodules. |

| Nodular dermatitis | Dense infiltrates of inflammatory cells in the dermis, often arranged in nodules. |

| Vesicular or bullous dermatitis | A space is formed in the tissue (usually with fluid accumulation) to form a blister. Blisters are categorised by their location (intraepidermal,usually subcorneal or suprabasal, or sub-epidermal). |

| Normal-looking skin | Clinical appearance or suspected diagnosis may guide pathologist to examine more carefully and to obtain special stains for surface fungi, mucin, mast cells etc. |

Common skin diseases

Common skin diseases have characteristic microscopic appearances. A biopsy is often not necessary in typical cases because a diagnosis may be made clinically. In less typical cases, the pathology may be very helpful. However histological diagnosis is not always specific in these cases because the numerous inflammatory skin diseases have overlapping features, and the appearances may be markedly altered by attempts at treatment and the chronicity of the condition.

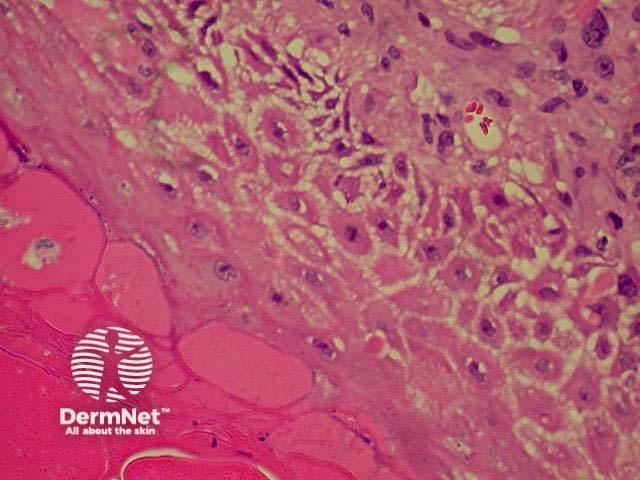

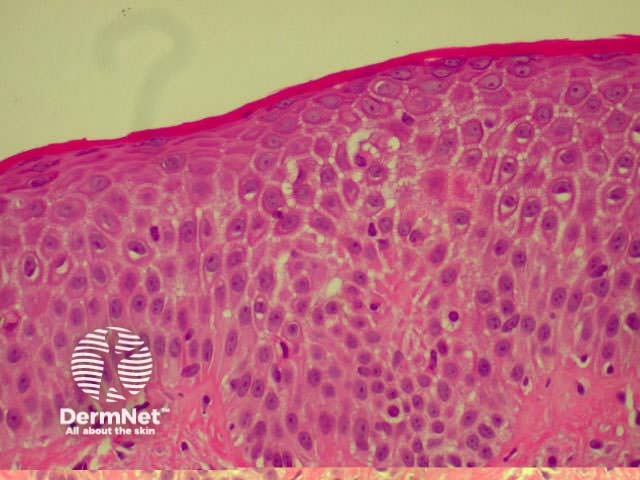

Eczema/dermatitis

A number of skin diseases are referred to as eczematous, in which there is diffuse ill-defined scaling and itching. Swelling and blistering may arise in acute eczema. Eczema or dermatitis are often synonymous. Link to a clinical description of dermatitis.

The histological features of eczema are:

- Spongiosis (which may be patchy) in acute eczema with associated lymphocyte exocytosis

- Acanthosis (thick skin) in chronic eczema

- Parakeratosis and a (usually superficial) perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate

- Excoriation and signs of rubbing (irregular acanthosis and perpendicular orientation of collagen in dermal papillae) in chronic cases (lichen simplex).

Spongiosis Spongiosis Spongiosis Spongiosis

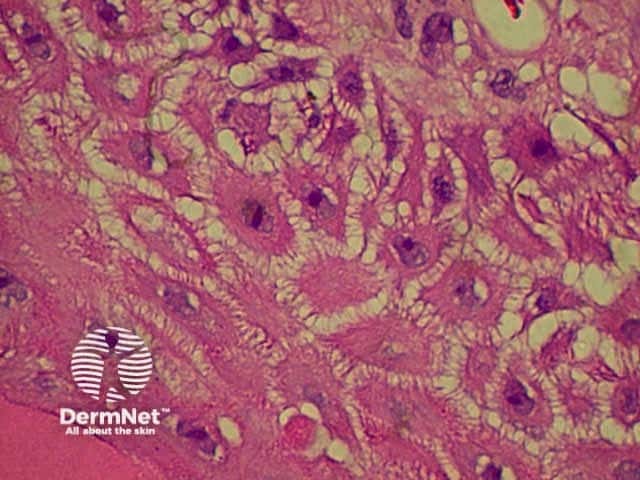

Psoriasis

There are various subtypes of psoriasis, a common dermatosis with well-demarcated erythematous scaly plaques. Link to a clinical description of psoriasis.

Due to the dynamic nature of psoriasis, this disease frequently does not show all classical histological features, but the typical changes of chronic plaque psoriasis are:

- Hyperkeratosis: mainly composed of parakeratosis, some orthokeratosis

- Neutrophils in stratum corneum (Munro's microabscesses) and squamous cell layer (spongiform pustules of Kogoj)

- Hypogranulosis

- Epidermis is thin over dermal papillae (thinned suprapapillary plates)

- Regular acanthosis, often with clubbed rete ridges

- Relatively little spongiosis

- Dilated capillaries in dermal papillae

- Perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate.

Parakeratosis Parakeratosis Parakeratosis Parakeratosis

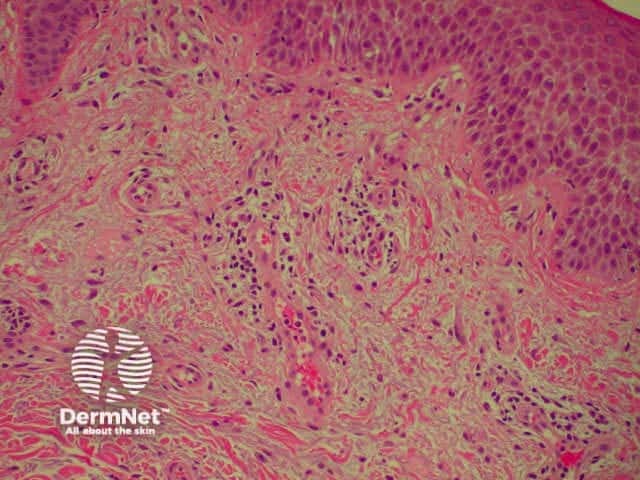

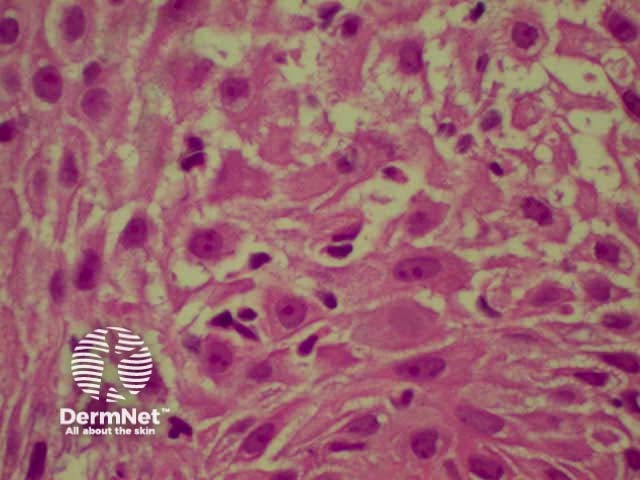

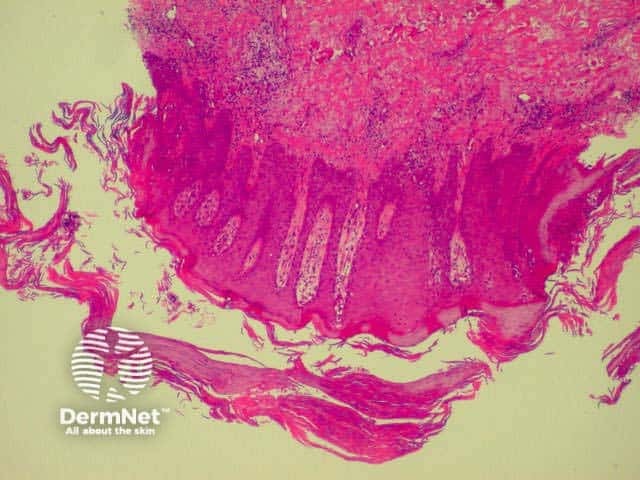

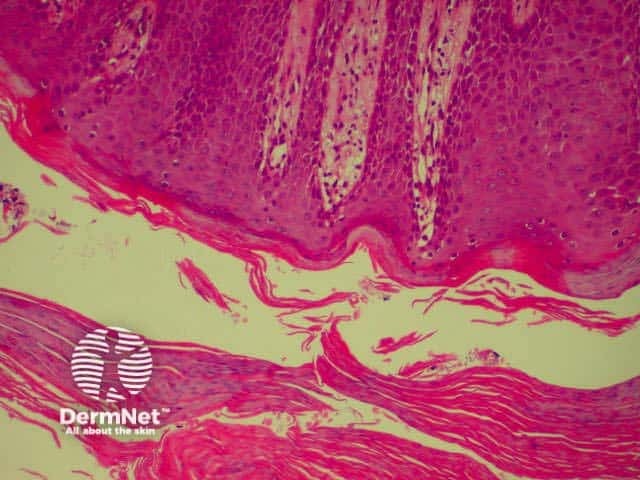

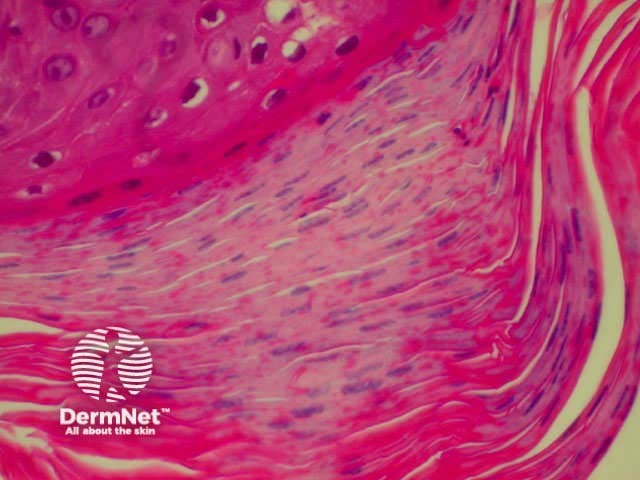

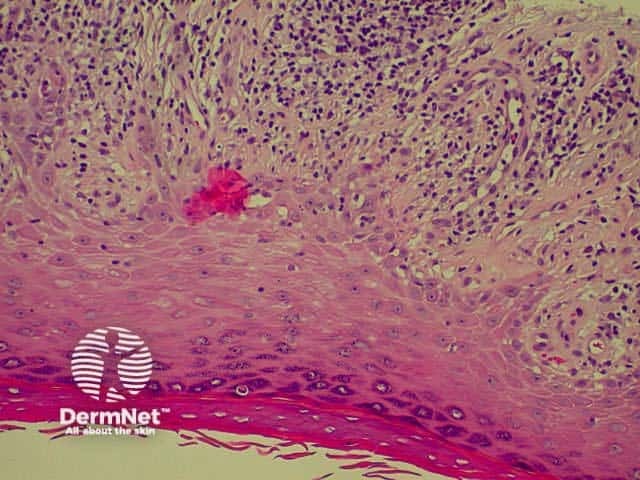

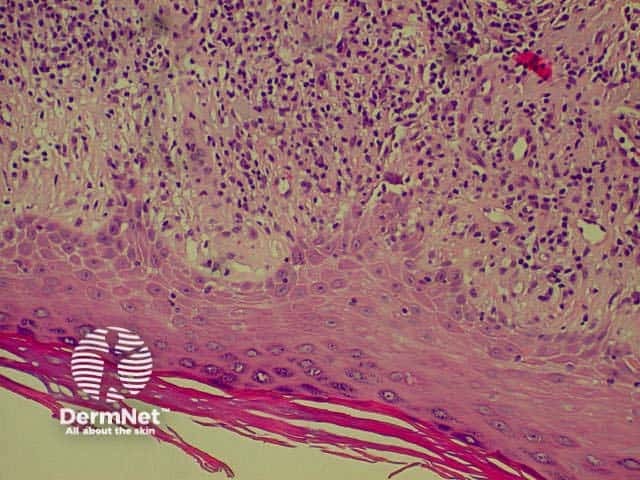

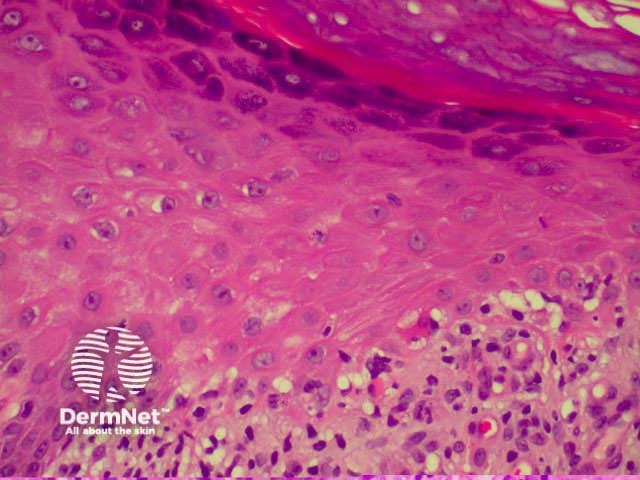

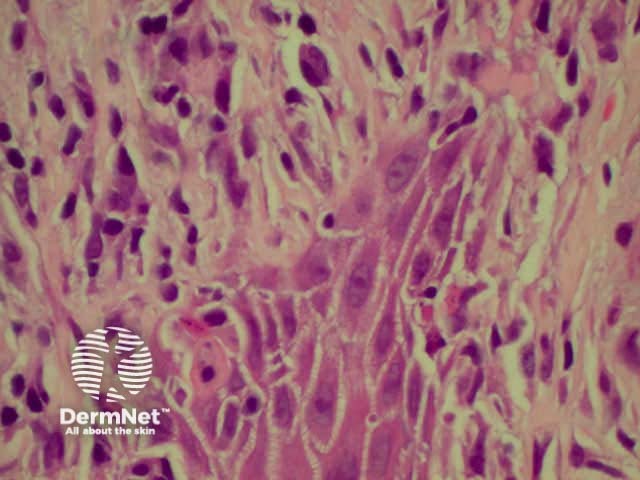

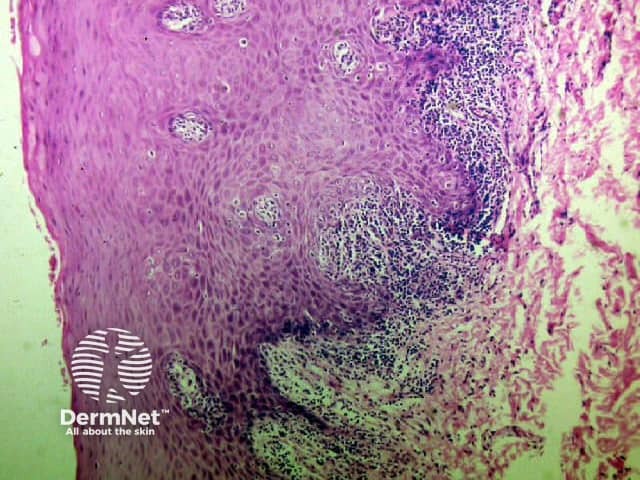

Lichen planus

Lichen planus is the idiopathic version of a group of lichenoid disorders characterised by scaling papules or plaques. Link to a clinical description of lichen planus.

The histological features of lichen planus are:

- Orthokeratosis

- Hypergranulosis

- Irregular acanthosis with saw-toothed rete ridges (older lesions)

- Colloid bodies in lower epidermis and upper dermis

- Liquefaction degeneration of the basal layer

- Lichenoid lymphohistiocytic infiltrate in upper dermis (interface dermatitis) and sometimes within the epidermis

- Melanin incontinence.

The majority of lymphocytes in the often dense infiltrate are memory cells, identified using histochemistry by positive CD8 and CD45 RO markers.

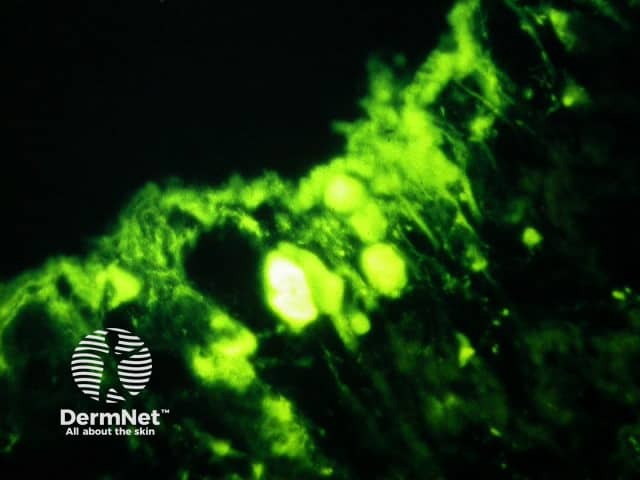

Direct immunofluorescence nearly always reveals fibrinogen within the colloid bodies. Occasionally IgM and complement are also detected. The immunofluorescence pattern is not diagnostic as the same reactants can also be seen in systemic lupus erythematosus and erythema multiforme.

Lichen planus Lichen planus Lichen planus Lichen planus Lichen planus Lichenoid inflammation

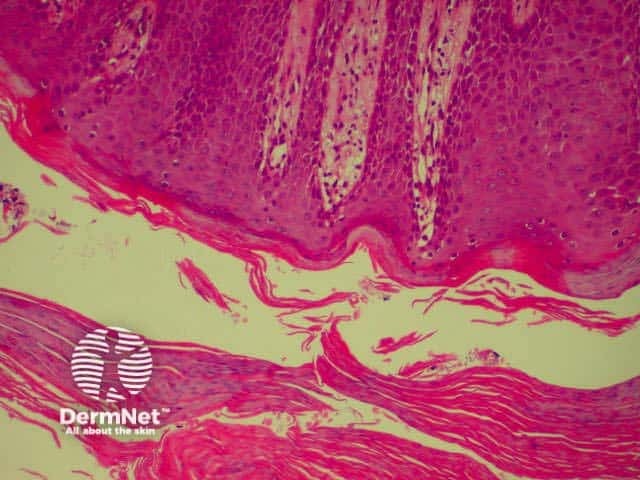

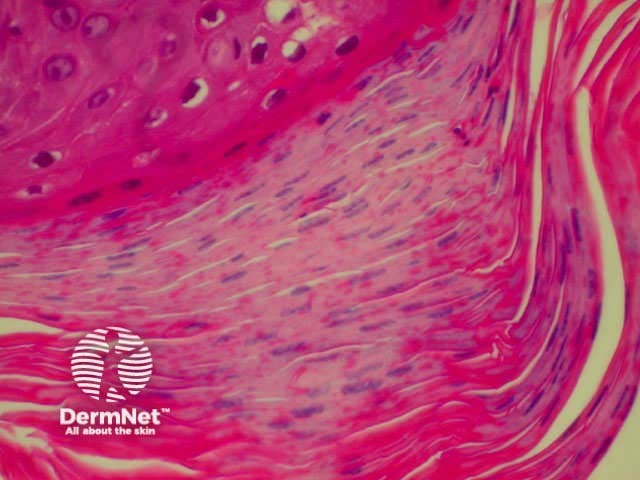

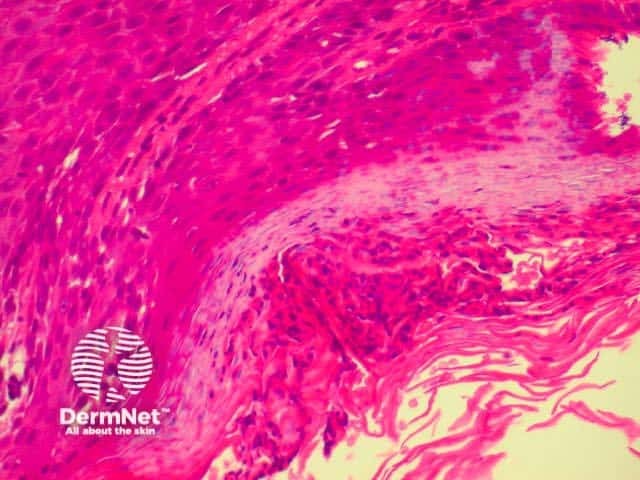

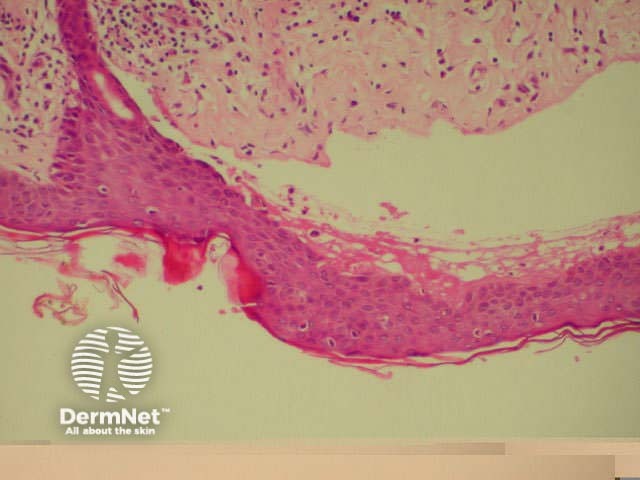

Bullous pemphigoid

Bullous pemphigoid is the most common subepidermal blistering disease. Link to a clinical description of bullous pemphigoid.

The histological features of bullous pemphigoid are:

- Subepidermal blister

- Viable roof over new blister, necrotic over an old blister

- Variable perivascular infiltrate (lymphocytes, histiocytes, eosinophils)

- Pre-bullous lesions may show spongiosis with eosinophil exocytosis (eosinophilic spongiosis).

Direct immunofluorescence reveals IgG and complement deposits in the basement membrane zone. (Biopsies for fluorescence should ideally be taken from erythematous but not yet bullous areas.) Indirect immunofluorescence will detect circulating antibodies. ELISA will be positive to 180 and 230kd BP antigens 2 and 1 respectively. Using skin separated by a salt splitting process, immunoreactants are seen to bind to the roof of the blister.

Bullous pemphigoid Bullous pemphigoid Bullous pemphigoid

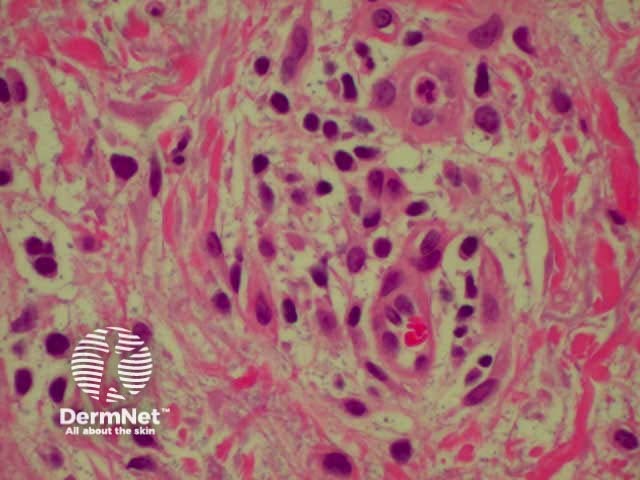

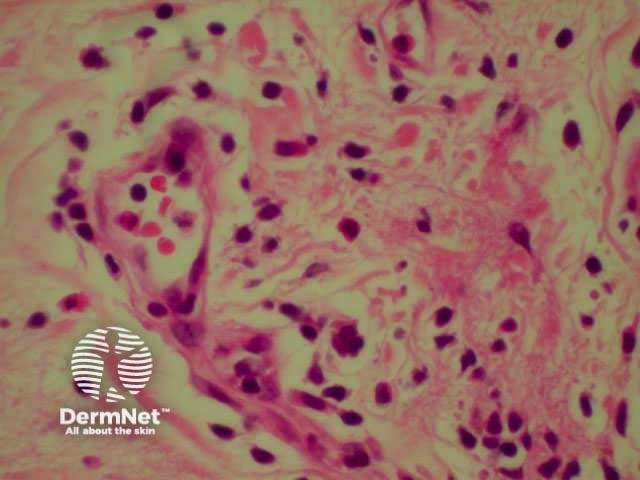

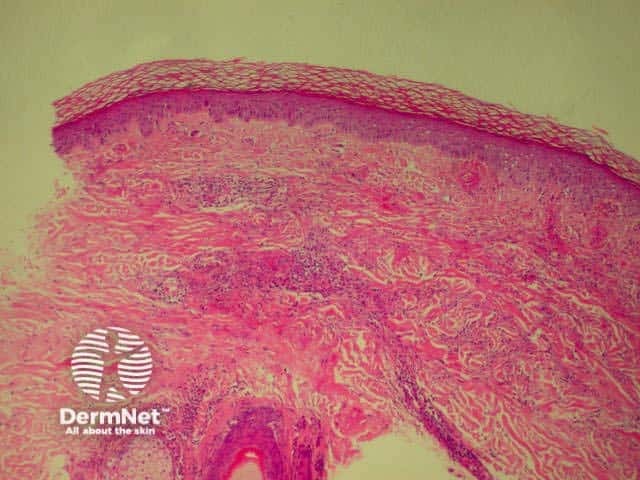

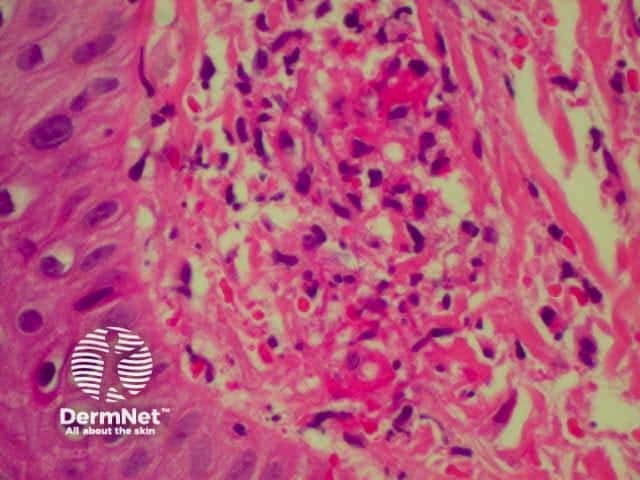

Vasculitis

Systemic vasculitis may affect the skin and vascular damage may be the main feature or a secondary feature in several skin diseases. Link to a clinical description of cutaneous vasculitis.

The histological features they have in common are:

- Vessel wall damage: necrosis, hyalinisation, fibrin

- Invasion of inflammatory cells into vessel walls

- Red cell extravasation (non-specific)

- Nuclear dust from leukocytoclasia of neutrophils (non-specific) typical of some types of vasculitis hence ‘leukocytoclastic vasculitis’)

- Severe cases may show ischaemic necrosis of the epidermis.

Leucocytoclastic vasculitis Leucocytoclastic vasculitis

Granuloma annulare

Granuloma annulare is the most common granulomatous disease of the skin. Its cause is unknown. Link to a clinical description of granuloma annulare.

The histological features of granuloma annulare are:

- Normal epidermis

- Central foci of dermal collagen degeneration (necrobiosis) and mucin accumulation

- Palisading of histiocytes

- Multinucleate giant cells

- Single-filing of inflammatory cells between collagen bundles (‘busy’ dermis).

Acne

Acne is a special form of folliculitis. Link to a clinical description of acne.

The histological features of acne are:

- Follicular plugging with entrapped bacteria and hairs

- Intrafollicular pustules

- Ruptured pilosebaceous apparatus

- Mixed perifollicular inflammatory infiltrate

- Sometimes abscesses, sinus tracts and scarring.

Potential errors in diagnosis

General pathologists and experienced dermatopathologists report what they see. Their job is easier if a trained and experienced specialist dermatologist provides them with a good history and clinical differential diagnosis and carefully selected large skin biopsy. However many histology reports are from poor samples with inadequate clinical information.

Inflammatory dermatoses may be localised or generalised but a biopsy only provides the pathologist with a small sample, which may not be representative of the disease as a whole.

- The biopsy may have been taken from the wrong lesion; patients may have more than one skin lesion or eruption.

- The biopsy may not contain diagnostic material.

- The biopsy may be fragmented or crushed.

- The technician may have incorrectly oriented the tissue resulting in horizontal rather than vertical sections.

- There may be other processing errors

- Incorrect diagnosis may arise because of inadequate information on the request form; different diseases with similar pathology may present at different ages or in different body sites. For example, pigmentation may be racial or pathological in origin.

- The microscopy may appear normal despite the quite obvious clinical disease. For example, if a cell infiltration cannot be identified on routine haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining.

- Changes may be too subtle to diagnose if the lesion is very early in its development.

- Secondary changes obscure primary pathology. These include excoriation, ulceration, healing, infection, necrosis and fibrosis.

- The thin section examined by the pathologist may not contain any part of the lesion present in another portion of the original specimen.

- Dense cellular infiltration may obscure the presence of another pathological feature, preventing its identification.

- Two quite different skin diseases might appear similar under the microscope.

Activity

Find a dermatopathology report of inflammatory skin disease. Rewrite the report in lay terms.

References

- Atlas of Dermatopathology. Rapini RP, Jordon RE. Year Book Medical Publishers, Inc. First edition 1998

On DermNet

Information for patients

Other websites

- University of Iowa College of Medicine DermPathTutor. A Tutorial in Dermatologic Pathology.

Books about skin diseases

See the DermNet bookstore.