Main menu

Common skin conditions

NEWS

Join DermNet PRO

Read more

Quick links

Dermatofibroma pathology — extra information

Lesions (benign) Diagnosis and testing

Dermatofibroma pathology

Author: Dr Harriet Cheng, Dermatology Registrar, Waikato Hospital, Hamilton, New Zealand; A/Prof Patrick Emanuel, Dermatopathologist, Auckland, New Zealand, 2013.

Introduction

Dermatofibroma is a common benign tumour also known as fibrous histiocytoma. There is debate as to whether dermatofibroma has a reactive or neoplastic origin. The clinical lesion is a firm tan-brown nodule most commonly found on the legs. A number of histological variants exist.

Histology of dermatofibroma

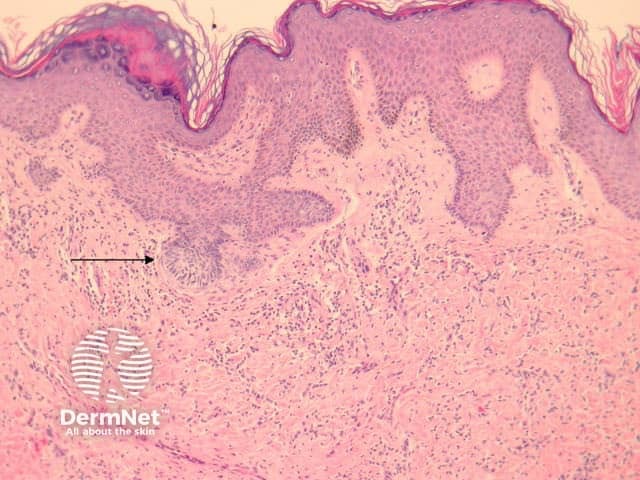

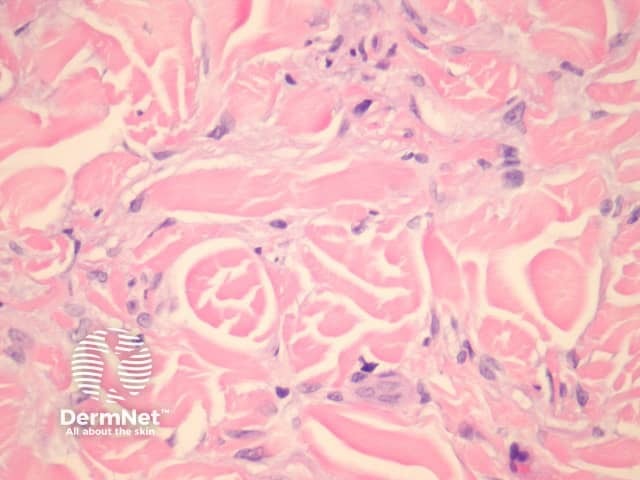

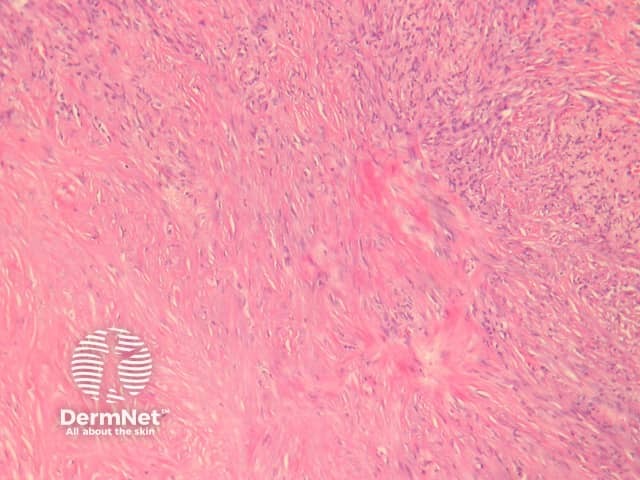

Dermatofibromas are dermal tumours characterised by a poorly defined proliferation of fibrohistiocytic cells within the dermis with an overlying grenz zone of sparing (figure 1). At the periphery of the lesion, there is entrapment of collagen (figure 2). The overlying epidermis may be acanthotic with increased basal layer pigmentation. Sometimes there is basaloid induction of the epidermis (figure 1, arrow) which may resemble small basal cell carcinoma or benign follicular tumours.

Figure 1

Figure 2

A number of histological variants of dermatofibroma are described below. Note, not all variants are mutually exclusive and more than one type may be present within the same lesion. Therefore, these variants probably just describe unusual features of dermatofibroma rather than distinctive pathologies. That said, understanding of these variants is useful for the clinician, as certain features suggest a more aggressive clinical course and therefore require special care, for example ensuring adequate excision margins and consideration of ongoing follow-up.

The term fibrous histiocytoma may be used interchangeably with dermatofibroma or to describe a dermatofibroma with a prominent storiform pattern.

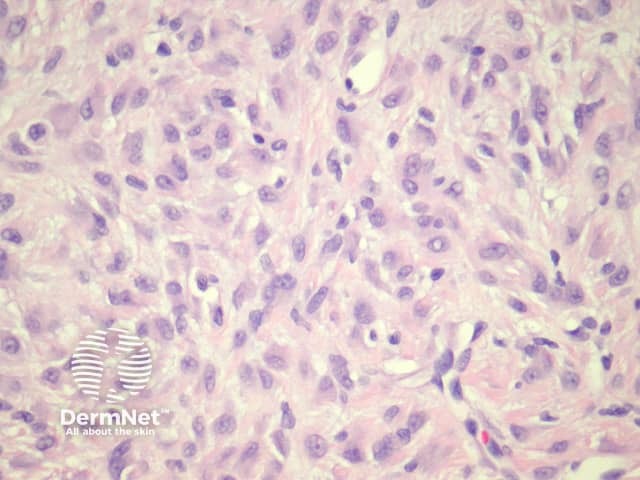

Cellular dermatofibroma

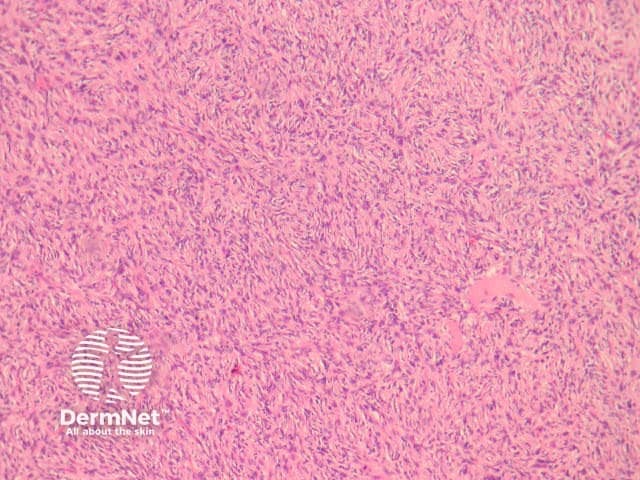

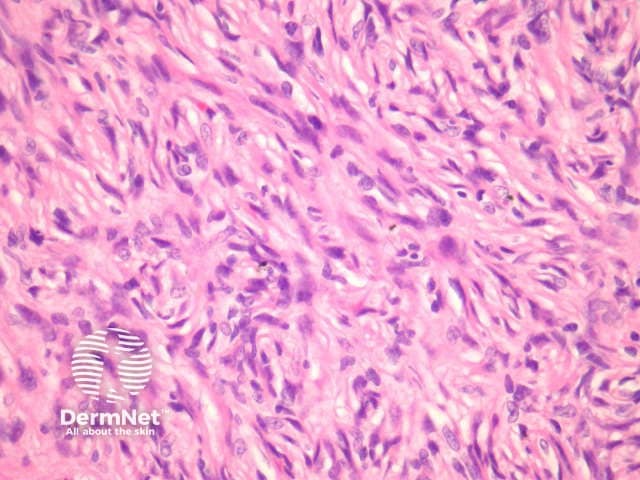

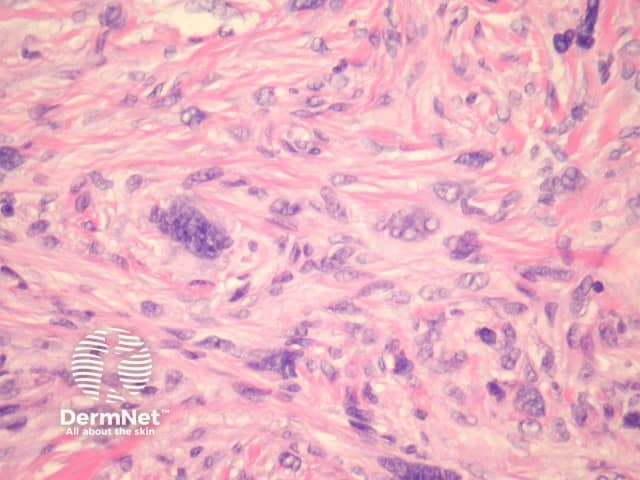

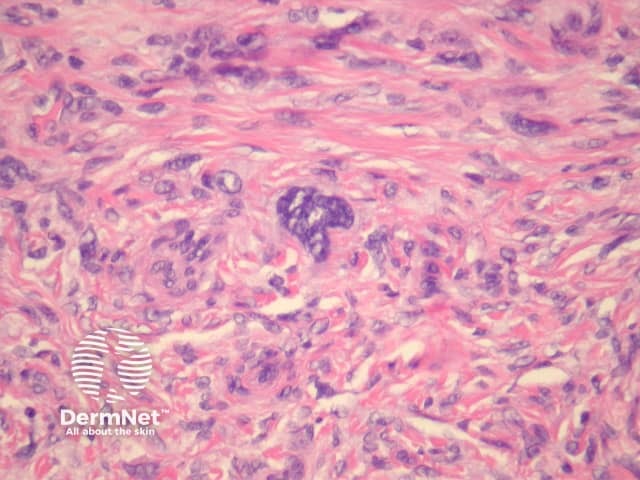

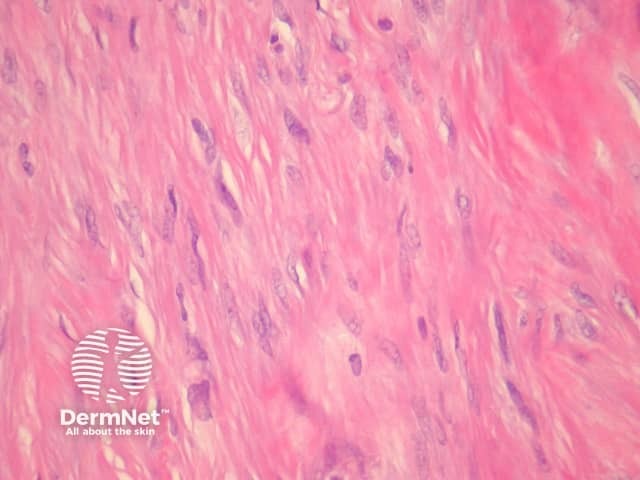

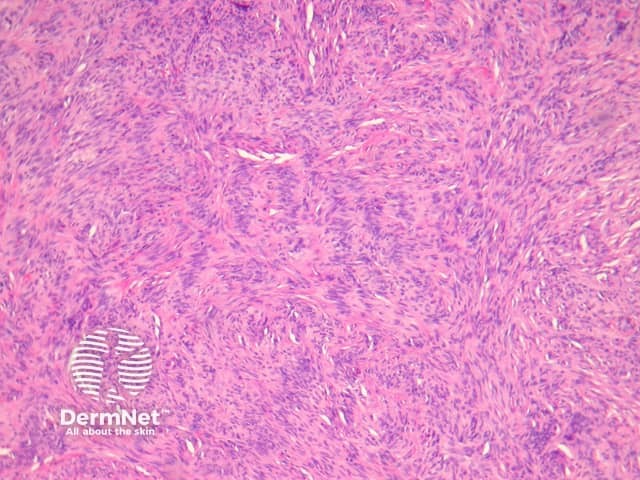

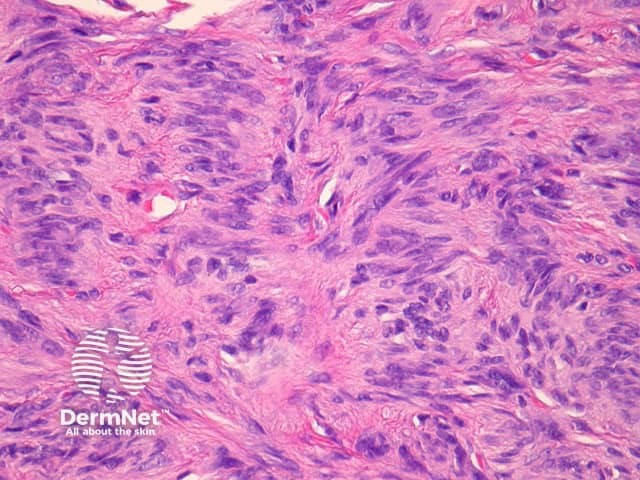

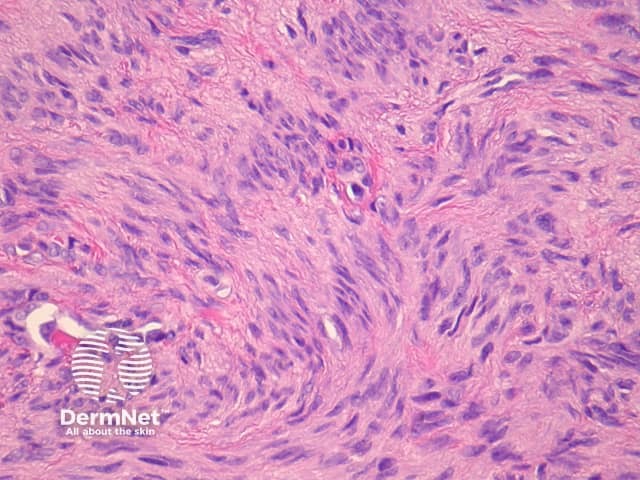

Compared with usual dermatofibroma, cellular dermatofibroma has an increased chance of recurrence following excision and metastasis is reported. Histologically, there is increased cellularity with a swirling, storiform pattern (figures 3,4). Peripheral entrapment of collagen is less prominent in this variant. There may be increased mitoses and extension to the subcutaneous fat, which are associated with more aggressive behaviour. Approximately 10% of cases show central necrosis.

Cellular dermatofibroma may resemble dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, which can be differentiated by its larger size, increased mitoses and marked involvement of the subcutis. CD34 is positive in dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans and is usually negative in dermatofibroma, although the cellular variant may have focal positivity, especially at the periphery of the lesion. A study of clonal karyotype abnormalities in dermatofibroma found cellular dermatofibromas were more likely to have karyotype abnormalities than common dermatofibromas.

Figure 3

Figure 4

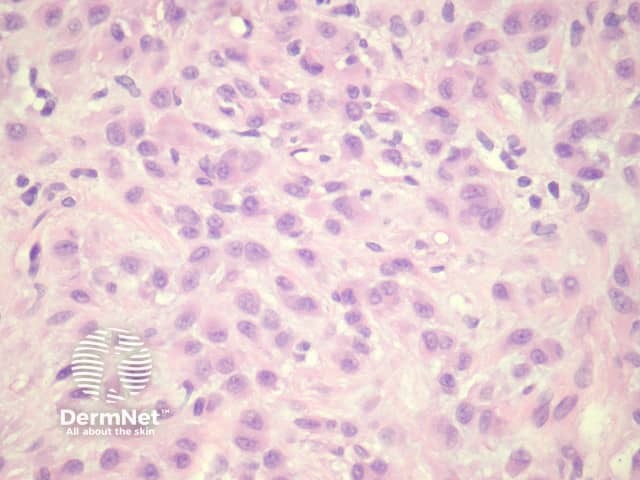

Epithelioid dermatofibroma

Epithelioid dermatofibroma is a well-recognised variant of dermatofibroma that may be confused with other benign and malignant mesenchymal lesions. The recent discovery of common ALK-1 translocation has led to the belief by some authorities that this is best considered a distinct entity rather than a form of dermatofibroma. Clinically it is distinctive, presenting as a polypoid red nodule. Like common dermatofibromas, epithelioid dermatofibromas are found most often on the leg. However, they can be found at unusual sites including the tongue.

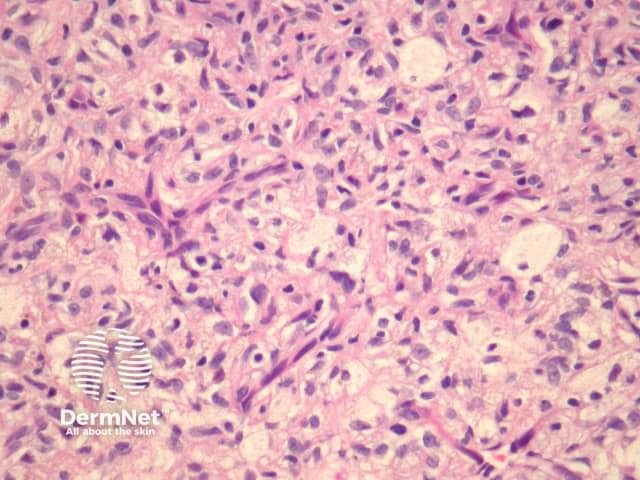

Sections through epithelioid dermatofibroma show a centrally located, circumscribed tumour underlying an epidermal collarette. The tumour is composed of cells arranged in sheets and sometimes a storiform pattern. Individual cells show epithelioid morphology with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm with round vesicular nuclei and prominent nucleoli (figures 5, 6). The cells may be markedly enlarged and display some nuclear atypia and mitoses. There is frequently an associated inflammatory cell infiltrate which can be helpful for the diagnosis.

Differential diagnosis includes other epithelioid tumours:

- Amelanotic melanoma — similar large epithelioid cells but generally displays more pleomorphism and epidermal involvement, and is S100 positive.

- Epithelioid sarcoma — granuloma-type clusters with necrosis, more atypia, keratin+.

- Other epithelioid dermal tumours — immunohistochemical studies can help exclude epithelioid vascular, smooth muscle, and histiocytic tumours.

Figure 5

Figure 6

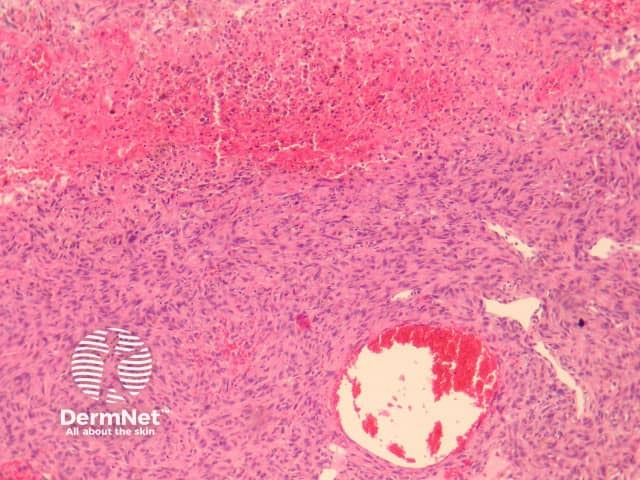

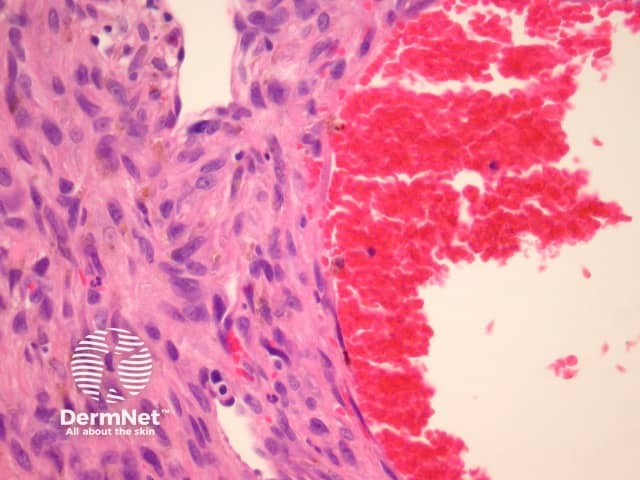

Aneurysmal dermatofibroma

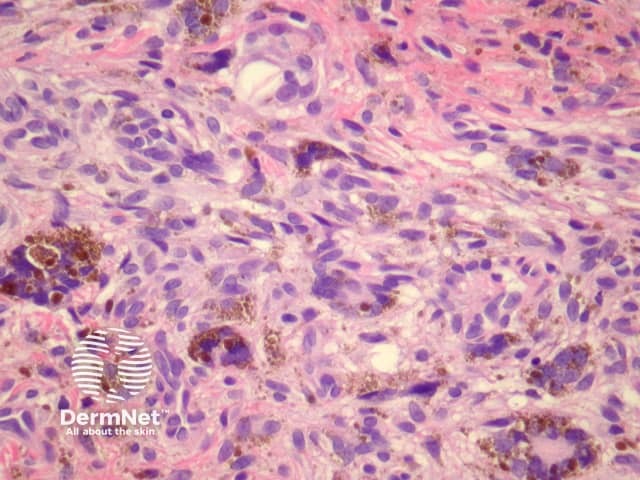

The clinical presentation of aneurysmal dermatofibroma is a rapidly growing blue-brown nodule. Periods of rapid growth are secondary to haemorrhage into the lesion. These tumours have a high recurrence rate and there is a report of aneurysmal dermatofibroma with regional lymph node involvement.

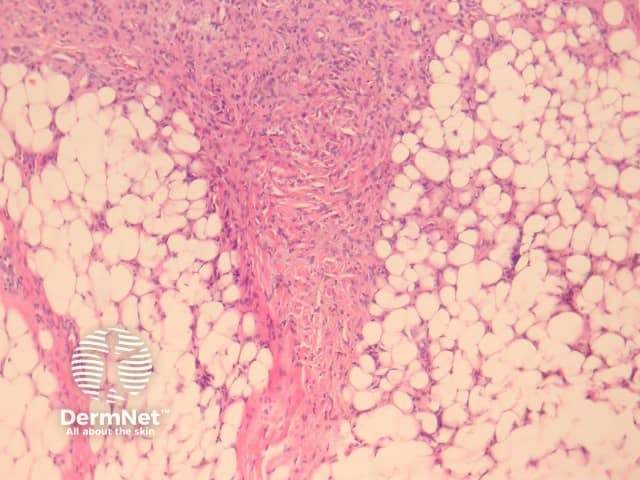

Histologically, there are cleft-like haemorrhagic spaces within the centre of the aneurysmal dermatofibroma that mimic vessels but lack an endothelial lining. The tumour itself tends to be fairly cellular (figure 7, 8). Haemosiderin deposition may be an additional feature. Aneurysmal dermatofibroma may be mistaken for a vascular tumour, however, clues to the diagnosis include surrounding features of dermatofibroma, and endothelial cell markers are positive in normal vessels only and not the aneurysmal spaces.

Figure 7

Figure 8

Atypical dermatofibroma

Atypical dermatofibroma is also known as dermatofibroma with monster cells or pseudosarcomatous dermatofibroma. There are focal areas within a common dermatofibroma consisting of large polymorphous cells with large nucleoli (‘monster cells’) (figures 9, 10).

Atypical dermatofibroma can be aggressive with rare reports of metastasis and death. However, many of these cases were described before modern immunohistochemical studies were available and may now be reclassified as sarcomas.

Figure 9

Figure 10

Haemosiderotic dermatofibroma

Haemosiderotic dermatofibroma may show extensive haemosiderin deposition (figure 11). Clinically, these may be pigmented and can mimic melanoma.

Figure 11

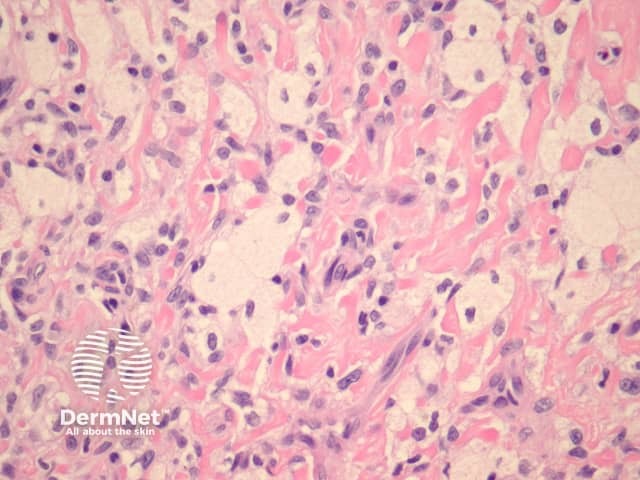

Lipidised dermatofibroma

Lipidised dermatofibroma is also known as ‘ankle type’ dermatofibroma due to a predilection for the lower leg. Histologically, foamy histiocytes predominate with marked hyalinization of collagen resembling amyloid (figure 12).

Figure 12

Fibrocollagenous dermatofibroma

Fibrocollagenous dermatofibroma has a prominent storiform or swirled pattern, with a predominance of collagen and fibroblast-like cells (figures 13, 14). This subtype seems to be more common in rare cases of disseminated dermatofibroma seen in immunosuppressed patients.

Figure 13

Figure 14

Clear cell dermatofibroma

Clear cell dermatofibroma has benign behaviour. It is considered by some experts to be a separate entity to dermatofibroma, as it has atypical morphology. The tumour consists of sheets of cells within the dermis and occasionally extending to the subcutis. Tumour cells have vesicular nuclei without significant atypia (figure 15). Histological features of clear cell dermatofibroma overlap with the recently described clear cell mesenchymal neoplasm, which is characterised by a dermal proliferation of cells with vesicular nuclei and clear to reticulated cytoplasm with or without cytological atypia and mitoses.

Figure 15

Deep fibrous histiocytoma

Deep fibrous histiocytoma resembles dermatofibroma histologically but affects the deep subcutis or soft tissues (figure 16). The limbs are the most frequent site followed by head and neck and then the trunk. Up to one in five deep fibrous histiocytomas recur following excision and there are 2 reported cases of metastasis and death.

Distinctive histological features of deep fibrous histiocytoma include a diffuse storiform pattern and haemangiopericytoma-like changes with staghorn-like thin-walled branching vessels in 40% of lesions. Unlike cutaneous dermatofibroma, these lesions are often CD34 positive.

Figure 16

Special studies of dermatofibroma

Immunohistochemical positive for Factor XIIIa.

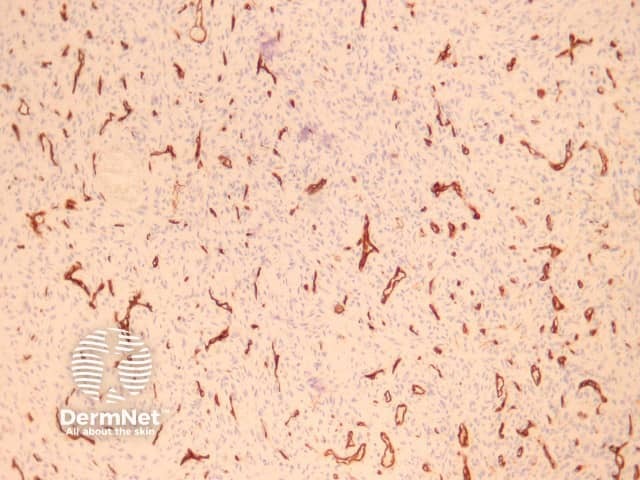

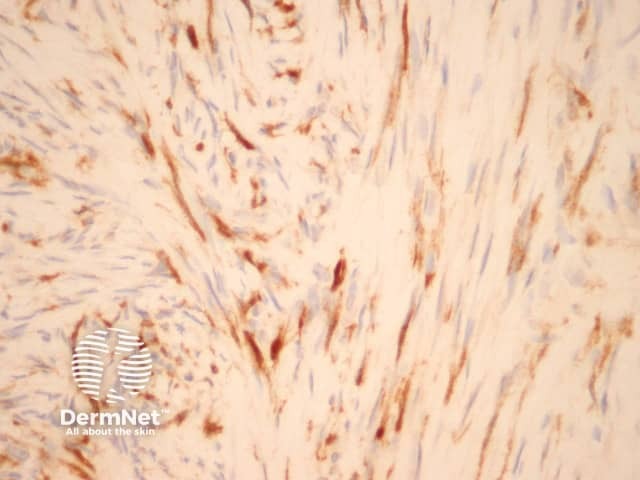

CD34 is usually negative in dermatofibroma but highlights the intermixed vessels and may be focally positive at the periphery of the lesion in the cellular variant (figure 17). Factor 13A usually stains the lesional cells (figure 18). There is variable positivity for CD68 and smooth muscle actin. An epithelioid fibrous histiocytoma is often positive with ALK-1.

Figure 17

Figure 18

Palisading dermatofibroma

Palisading dermatofibroma is characterised by prominent palisading of nuclei, mimicking Verocay bodies seen in schwannoma. Differentiating features from schwannoma include the lack of a capsule, and staining for S100 is negative (S100 is positive in schwannoma) (figures 19, 20, 21).

Figure 19

Figure 20

Figure 21

Atrophic dermatofibroma

Atrophic dermatofibroma is likely to represent the end-stage of a dermatofibroma and often presents clinically as a depressed lesion. Histologically, tumour cells are sparsely distributed amongst abundant hyalinised collagen.

References

- Dermatology (Third edition, 2012). Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV

- Weedon’s Skin Pathology (Third edition, 2010). David Weedon

- Pathology of the Skin (Fourth edition, 2012). McKee PH, J. Calonje JE, Granter SR