Main menu

Common skin conditions

NEWS

Join DermNet PRO

Read more

Quick links

Australian box jellyfish stings — extra information

Australian box jellyfish stings

Author: Dr Kirsten Due, General Practitioner, South Australia, Australia. DermNet Editor in Chief: Hon A/Prof Amanda Oakley, Dermatologist, Hamilton, New Zealand. Copy editor: Maria McGivern. May 2017.

Images courtesy of Professor Bart Currie, Menzies School of Health Research, Darwin, Northern Territory, Australia.

Introduction Demographics Mechanism Presentation Systemic signs Causes - death from envenomation Immunology Diagnosis Treatment Therapeutic uses

What is the Australian box jellyfish?

The Australian box jellyfish or Chironex fleckeri, more commonly known as a sea wasp or ‘stinger’, is a species of venomous and deadly box jellyfish found off the coast of tropical Australia.

The Australian box jellyfish is an invertebrate marine animal of the phylum cnidaria (Gk. ‘stinging object’), named in honour of radiologist Dr Hugo Flecker (1884–1957). Cnidaria (‘nid-AIR-ee-ah’) are vast in variety. They comprise four main classes:

- Hydrozoa, such as the Portuguese man of war (also known as the bluebottle)

- Anthozoa, such as anemones, corals and sea pens

- Scyphozoa, such as the true jellyfish

- Cubozoa, such as box jellies, including the "major" Australian box jellyfish — C. fleckeri.

Of the 10,000 known species of Cnidaria, about 100 are potentially dangerous to humans. The Australian box jellyfish, has been responsible for over 70 fatal stings or ‘envenomings’ since 1883. Cubozoans also include several species of four tentacled box jellyfish that cause Irukandji syndrome.

Australian box jellyfish specimens have weighed up to 6 kg; they are composed of a large umbrella-like bell with four bundles of tentacles arising from the corners of the bell. The box jellyfish is difficult for victims to see, and harder to avoid, with their near-transparent tentacles extending up to 300 mm. Their stings injure the skin and can cause severe systemic effects. They feed on small prawns.

The Australian box jellyfish is found in coastal waters from northern Australia but its distribution can now be widened to include nearby areas of the Indo-West-Pacific Ocean. Their northern-most reach has yet to be found, and their overall biogeography is uncertain.

Until recently, it was thought that Australian box jellyfish were rare in deep waters as marine surveys of the Great Barrier Reef found few away from the shore or deeper than 5 m. However, an opportunistic deep-sea video study in North-western Australia found large numbers at depths of 39–56 m (64 in a 1500 m tow or 0.05 m2).

The Australian box jellyfish

Chironex fleckeri

Who is affected by Australian box jellyfish stings?

- Box jellyfish are most commonly present in tropical Australian waters from November to April each year, with 8% of stings occurring outside this period.

- Stings most commonly occur in adult men in water less than 100 mm deep.

- About 37% of Australian box jellyfish stings occur in children.

- Stings most often occur in people entering the water between 3 and 6 pm, with an outbound tide.

- Rain and strong winds, but not cloudy weather, are a deterrent to the jellyfish.

What is the mechanism and toxicology of Australian box jellyfish stings?

Stings from the Australian box jellyfish are difficult to study because:

- It is difficult to collect pure venom without contamination — until recently, the most widely used method of toxin extraction involved pulverising the tentacles and nematocysts (or ‘stinging cells’)

- The toxin proteins are fragile and easily degraded by unfavourable temperatures and pH

- The venom is spread by tiny nematocysts, each containing picograms (trillionths of a gram) of proteins.

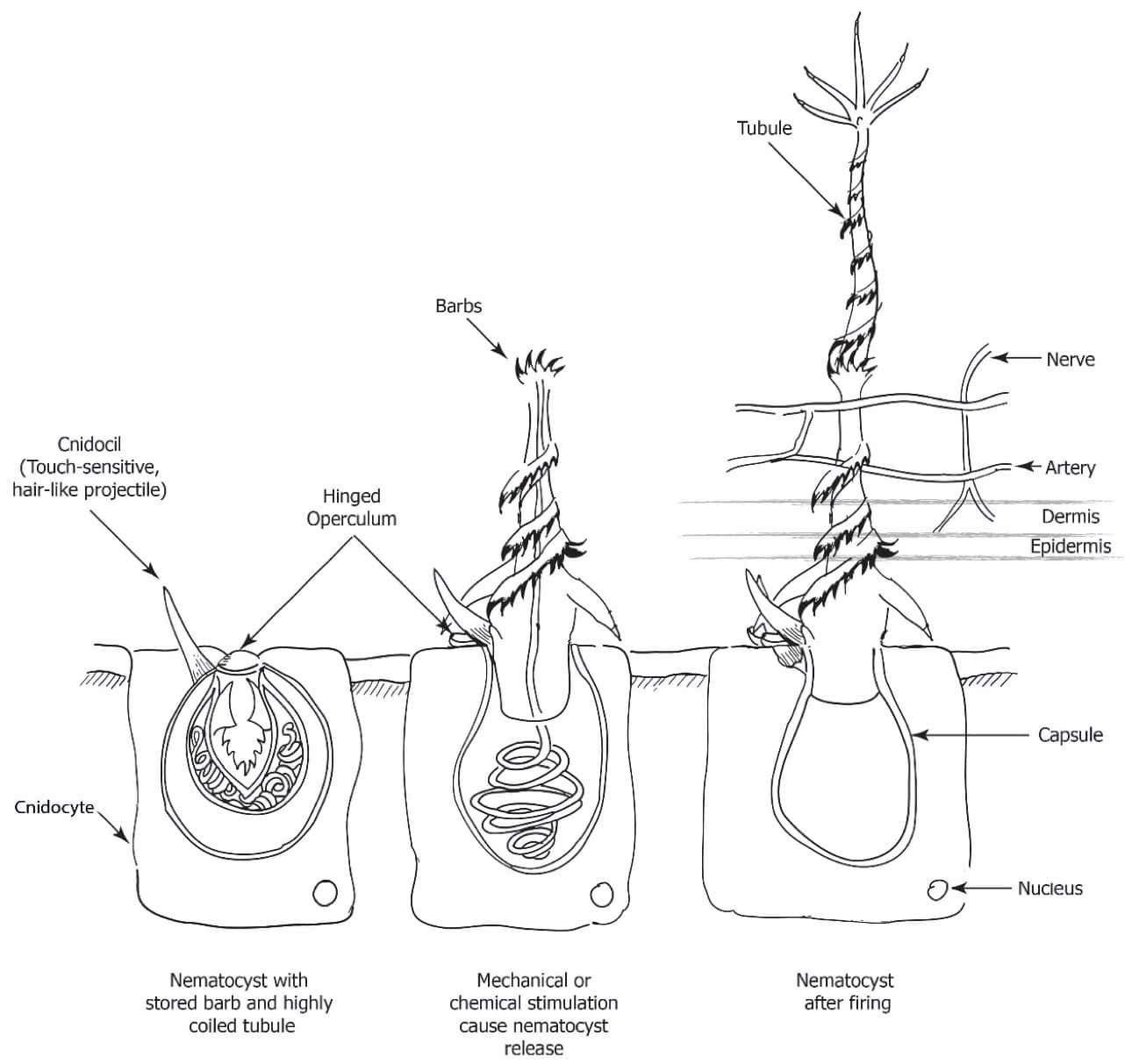

Envenomation (or stinging) occurs when human skin contacts the thousands of densely packed nematocysts that line the jellyfish tentacles. Within 700 Ns of contact, the nematocyst capsules fire thousands of barbed, poison-filled darts. These travel 67 km/hour with an impact pressure on the epidermis of 7.7 GPa (about 1,116,790.5 psi).

Each poison-filled dart is filled with porins (transmembrane proteins), neurotoxic peptides and bioactive lipids.

Source: Marine Drugs

What are the local signs of Australian box jellyfish envenomation?

The Australian box jellyfish toxin is injected into the skin. It has direct effects on muscle and nerves, and can cause chronic immunological complications.

Most Australian box jellyfish stings are a nuisance rather than a medical threat. The seriousness of the sting relates to the size of the box jellyfish (those with a bell over 150 mm are considered highly dangerous).

Skin symptoms occur immediately upon contact and include:

- Exquisite pain, itch and welts at the area of contact

- Linear welts are a brownish-purple colour and up to 10 mm in width

- Lesions may be visibly haemorrhagic

- Blisters may form within minutes of contact

- Full-thickness skin necrosis can occur 1–2 weeks later

- It can be followed by whip-like hypopigmentation or hyperpigmentation.

The response to Australian box jellyfish envenomation varies from person to person, depending on how well the dermis can clear irritant chitins (the jellyfish exoskeleton) from the skin.

Australian box jellyfish stings (Darwin Harbour)

Early skin lesion (MAS-patient1)

3 days later (MAS-patient1)

Snake-like inflammatory lesions from box jellyfish stings

What are the systemic signs of Australian box jellyfish envenomation?

Systemic features of Australian box jellyfish envenomation may include:

- Difficulty breathing

- A drop in blood pressure

- Irritability and restlessness

- Faintness and collapse

- Cardiac arrhythmias

- Cardiac arrest.

If the total estimated length of welts is over 700 mm, unconsciousness follows rapidly, culminating in a painful death after 5–20 minutes.

With their lower body-mass, children are most vulnerable.

What causes death from Australian box jellyfish envenomation?

Death from Australian box jellyfish envenomation is largely due to the rapid cardiovascular effects of pore-forming toxins. Autopsies reveal pulmonary oedema.

What are the immunological aspects of Australian box jellyfish envenomation?

The spiny darts that explode into the epidermis are made up of collagens, glycoproteins and polysaccharides. These may trigger antigenic and innate immune responses, separate from the toxins they carry. Angioedema and anaphylaxis may occur.

How is Australian box jellyfish envenomation diagnosed?

Diagnosis of Australian box jellyfish envenomation depends on noting the typical clinical features and sighting a responsible jellyfish. A definitive diagnosis is based on the characteristic nematocysts from the Australian box jellyfish being found. Sticky tape can be used to collect skin samples for research and identification purposes.

What is the treatment for Australian box jellyfish stings?

First-responder treatment includes getting the person out of the water while not endangering the rescuers.

A clothed rescuer is unlikely to sustain envenomation as the nematocysts from the Australian box jellyfish do not effectively puncture even thin clothing.

- Once on shore, apply vinegar for at least 30 seconds after envenomation; this deactivates penetrating nematocysts. Many tropical Australian beaches contain vinegar stations with clearly marked bottles for public use in case of marine envenomation. (Vinegar is one of a few chemicals, including ethanol, known to cause massive toxin discharge in a research, in-vitro context but not in the rescue setting, where vinegar prevents further toxin discharge when applied to the skin.)

- Pluck off the remaining tentacles using the fingertips (the box jellyfish nematocysts do not penetrate the thicker palmar skin).

- Basic and advanced life support may be required, depending on the degree of envenomation and morbidity seen in each case.

Heat is not recommended as part of standard treatment, although it can reduce the venom lethality when maintained at over 43 C as the use of heat may deter more valuable efforts at symptom control and resuscitation.

Do not apply pressure immobilisation bandages, as these may trigger further toxin discharge.

What is the role of antivenom?

- Intravenous antivenom has been available since the 1970s.

- Antivenom is reserved for intractable pain, potential severe scarring and cardiorespiratory instability.

- It reduces cardiac morbidity and lessens pain, local tissue damage and scarring.

- Up to 2013, no adverse reactions to antivenom had been reported.

What are the therapeutic uses for Australian box jellyfish venom?

Cnidarian venoms have been investigated as a potential source of novel bioactive therapeutic compounds. Collagen from the Australian box jellyfish bell enhances immunoglobulins M and G, interferon and tumour necrosis factor production by human lymphocytes, as well as enhancing inflammatory cytokine secretion, antibody secretion and causing population changes in immune cells.

References

- Montgomery L, Seys J, Mees J. To pee, or not to pee: a review on envenomation and treatment in European jellyfish species. Mar Drugs 2016; 14(7): 127. DOI: 10.3390/md14070127. Journal

- Pearn JH. Flecker, Hugo (1884–1957). Australian Dictionary of Biography. First published 1996. Available at: http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/flecker-hugo-10199 (accessed November 2016).

- University of California Museum of Paleontology. Introduction to cnidaria: Jellyfish, corals, and other stingers. Available at: www.ucmp.berkeley.edu/cnidaria/cnidaria.html (accessed November 2016).

- Currie BJ, Jacups SP. Prospective study of Chironex fleckeri and other box jellyfish stings in the “Top End” of Australia’s Northern Territory. Med J Aust 2005; 183: 631–6. Journal

- Australian Marine Stinger Advisory Services. Box jellyfish and Irukandji deaths in Australia. 2014. Available at: www.stingeradvisor.com/boxydeaths.htm (accessed November 2016).

- Warrell DA. Venomous and poisonous animals. In: Farrar J, Junghanss T, Kang G, Lalloo D, White NJ eds). Manson's tropical diseases, 23rd edn. Elsevier, 2014.: 1096–127.

- Cegolon L, Heymann WC, Lange JH, Mastrangelo G. Jellyfish stings and their management: a review. Mar Drugs 2013; 11(2): 523–50. DOI: 10.3390/md11020523. Journal

- Tibballs, J. Australian venomous jellyfish, envenomation syndromes, toxins and therapy. Toxicon 2006; 48: 830–59. DOI: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2006.07.020. PubMed

- Kingsford MJ, Seymour JE, O’Callaghan MD. Abundance patterns of cubozoans on and near the Great Barrier Reef. Hydrobiologia 2012; 690: 257–68. DOI: 10.1007/s10750-012-1041-0. Abstract

- Keesing JK, Strzelecki J, Stowar M, et al. Abundant box jellyfish, Chironex sp. (Cnidaria: Cubozoa: Chirodropidae), discovered at depths of over 50 m on western Australian coastal reefs. Scientific Reports 2016; 6: 22290. DOI: 10.1038/srep22290. Journal

- Lee H, Kwon YC, Kim E. Jellyfish venom and toxins: a review. In: Gopalakrishnakone P, Haddad Jr. V, Kem WR, Tubaro A, Kim E (eds). Marine and Freshwater Toxins. Springer, 25 September 2015: 1–14. Abstract

On DermNet

Other websites

- Cnidarians: simple animals with a sting! — Ocean Research Group

- First aid treatment of jellyfish stings — MarineMedic.com

Books about skin diseases