Main menu

Common skin conditions

NEWS

Join DermNet PRO

Read more

Quick links

Bee and wasp stings — extra information

Bee and wasp stings

Author: Dr Beth Wright, Core Medical Trainee, Bristol, United Kingdom, 2013.

DermNet Update May 2021. Copy edited by Gus Mitchell

Introduction Demographics Causes Clinical features Complications Diagnosis Differential diagnoses Treatment Outcome

What are bee and wasp stings?

Bees (Apidae) and wasps (Vespidae) are venomous stinging insects (class Hymenoptera). A honeybee mostly only attacks when it feels threatened, inflicting a single painful toxic sting. The Africanised ‘killer’ bee, however, is highly aggressive, resulting in massive bee attacks throughout most of the Americas where it has become endemic. Wasps also are aggressive, sting to attack, and can sting multiple times.

Bee sting reaction

Bee venom reaction

Multiple wasp stings

Who gets bee and wasp stings?

Bee and wasp stings mostly occur outdoors, usually around the home. Beekeepers are particularly susceptible, typically receiving many stings over their working lifetime.

In Europe, the prevalence of systemic reactions to bee and wasp stings in the adult population is 0.3–8.9%, higher in beekeepers, lower in children, and are a major cause of anaphylaxis accounting for nearly 50% of adult cases and 20% in children.

What causes bee and wasp stings?

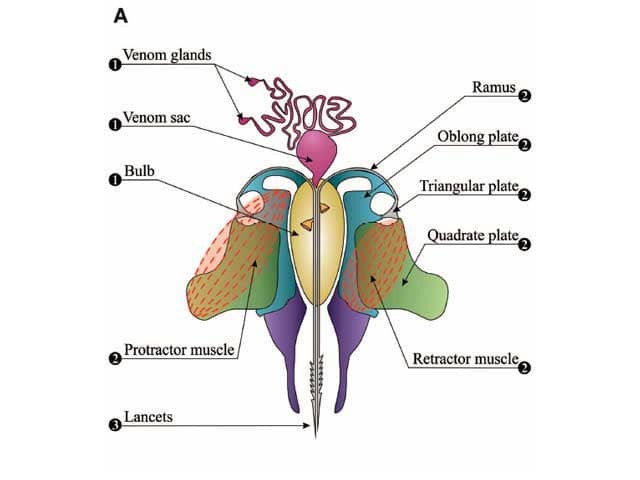

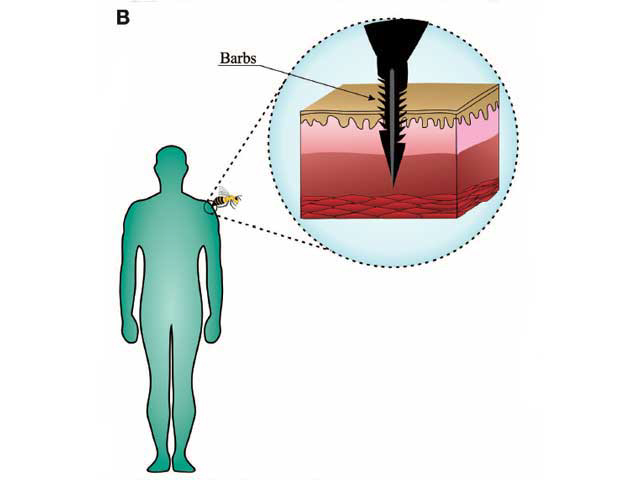

The bee stinger consists of muscles, piercing stylet and lancets, and the venom sac, glands, and bulb. Barbs on the lancets make it impossible for the bee to retract its stinger, leaving the stinger embedded in the wound after the bee escapes. An individual bee therefore can only sting once and dies within a day or two. At least 90% of the venom is delivered in the first 20 seconds. Melittin is the most toxic compound in bee venom, causing most of the pain but only minor allergic reactions. Hyaluronidase is a potent allergen and is responsible for the rapid distribution of the venom in tissues.

Wasps can sting multiple times as they do not leave their stinger behind in the skin.

The severity of the reaction depends on the age and size of the victim, the number of stings, previous sensitisation, and co-morbidities such as atopy, mastocytosis, and immune status.

Honey bee

Bee sting apparatus

Barbs on the lancet prevent withdrawal from the skin

Diagrams from: Pucca MB, Cerni FA, Oliveira IS, et al. Bee updated: current knowledge on bee venom and bee envenoming therapy. Front Immunol. 2019;10:2090.

What are the clinical features of bee and wasp stings?

A bee or wasp sting causes an immediate sharp pain that usually only lasts for a few seconds, followed by redness, swelling, pain, and, following a bee sting, the embedded stinger.

- Local inflammatory reaction

- Non-allergic individual

- Localised pain, swelling, redness, itch

- Minor localised reaction resolves within 24 hours

- Large localised reaction (>10cm) may persist for up to one week

Bee sting reaction

Wasp sting reaction

Redness and swelling due to a bee sting

-

Allergic manifestations

- IgE-dependent type I hypersensitivity [see Allergies explained]

- Onset 10 minutes after sting

- Urticaria, angioedema, itch

- Vomiting and diarrhoea

-

- Bronchoconstriction

- Abdominal cramping and vomiting

- Cardiorespiratory arrest within 5–10 minutes

-

Systemic toxic reactions (envenomation)

- Usually follows 500 or more stings

- Dizziness, nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea

- Cardiac, liver, renal, muscle damage

- Can be fatal

What are the complications of bee and wasp stings?

- Blistering

- Secondary bacterial skin infection, including cellulitis and lymphangitis

- Persistent reaction lasting weeks or months

- Vasculitis, serum sickness, neurological effects

- Impact on quality of life — anxiety resulting in social restriction.

Wasp sting reaction persisted for more than 6 weeks

Wasp sting reaction causing localised vasculitis with purpura

Blistering reaction to a bee sting

How is bee and wasp sting allergy diagnosed?

Both skin testing and serologic tests should be performed on patients with a history of a systemic reaction to a bee or wasp sting, and considered for those with large local reactions.

- Allergy skin testing: skin prick testing and intradermal testing using purified venom at least two weeks after a sting reaction.

- Serology: serum IgE testing for antibodies against specific insect venoms.

- Basophil activation test: useful if the skin test is negative but the sIgE is positive.

- Baseline serum tryptase: to identify an unrecognised mast cell disorder which predisposes to severe sting reactions.

What is the differential diagnosis for bee and wasp stings?

- Other arthropod bites and stings

- Other causes of anaphylaxis

- Cellulitis

What is the treatment for bee and wasp stings?

Prevention

- Avoid situations where bee and wasp stings may occur

- If a wasp nest or bee swarm is found near the home, employ a professional to remove it

- Wear protective clothing

- Apply insect repellent such as DEET

Treatment of localised site reactions

If the reaction is mild, bee stings should be treated by first removing the stinger:

- Place a firm edge such a knife or credit card against the skin next to the embedded stinger

- Apply constant firm pressure and scrape across the skin surface to remove the stinger. This is preferred to using tweezers or fingers, which can accidentally squeeze more venom into the patient.

Treatment of the sting site:

- Clean the site with water or disinfectant

- Try not to scratch or rub

- Apply cold compress to reduce pain and swelling

- Simple analgesia

- Topical steroid cream or calamine lotion may be applied several times a day until symptoms subside

- Oral antihistamines if required

- Large localised reaction with severe swelling may require oral steroids.

Treatment for systemic reactions

If a bee or wasp sting causes a severe reaction or anaphylaxis, urgent medical attention should be sought.

- Adrenaline (eg, EpiPen®) should be administered if available for anyone with signs of shock, breathing difficulty, or airway swelling.

- In hospital, Advanced Life Support (ALS) protocols should be followed.

- Those who are at risk of anaphylaxis should be supplied with an EpiPen and counselled, along with their close relatives, responsible adults, or carers, about how and when to use it.

In the Americas where the Africanised bee has become endemic, any individual who has had more than 50 stings (‘massive stinging’) should be observed for anaphylaxis and toxic envenomation.

Venom immunotherapy desensitisation

Gradually increasing doses of insect venom are injected subcutaneously to induce immunological tolerance every few weeks for 3–5 years; continue lifelong in clonal mast cell disorders with history of severe reaction or very severe anaphylaxis reactions. Protection usually lasts 1–3 years after discontinuation.

Insect venoms are commercially available for honey bee, paper wasp, and yellow jacket European wasp.

A Cochrane review reported venom immunotherapy significantly reduces the risk of systemic and large local reactions, and is likely to reduce the risk of anaphylaxis, improving quality of life.

Venom immunotherapy can be recommended for:

- Children with systemic sting reactions not limited to the skin

- Adults with systemic reactions including those limited to the skin

- High risk factors including beekeepers, patients with clonal mast cell disorders

- Impaired quality of life following sting reactions

- NOT recommended for toxic reactions or those sensitised but with no clinical symptoms.

What is the outcome for bee and wasp stings?

The majority of bee and wasp sting reactions are localised and resolve in hours to days. Episodes are usually rare and simple preventative measures are all that is required. However, sensitisation can develop with repeat episodes, such as can happen to beekeepers and agricultural workers. Following an episode of anaphylaxis, the risk of subsequent anaphylaxis is less than 50%, lower in children.

Bibliography

- Bilò MB, Tontini C, Martini M, Corsi A, Agolini S, Antonicelli L. Clinical aspects of hymenoptera venom allergy and venom immunotherapy. Eur Ann Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019;51(6):244–58. doi:10.23822/EurAnnACI.1764-1489.113. Journal

- Boyle RJ, Elremeli M, Hockenhull J, et al. Venom immunotherapy for preventing allergic reactions to insect stings. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;10:CD008838. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008838.pub2. Journal

- Ludman SW, Boyle RJ. Stinging insect allergy: current perspectives on venom immunotherapy. J Asthma Allergy. 2015;8:75–86. doi:10.2147/JAA.S62288. Journal

- McGain F, Harrison J, Winkel KD. Wasp sting mortality in Australia. Med J Aust. 2000;173(4):198–200. doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.2000.tb125600.x. PubMed

- Pucca MB, Cerni FA, Oliveira IS, et al. Bee updated: current knowledge on bee venom and bee envenoming therapy. Front Immunol. 2019;10:2090. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2019.02090. Journal

- Rahimian R, Shirazi FM, Schmidt JO, Klotz SA. Honeybee stings in the era of killer bees: anaphylaxis and toxic envenomation. Am J Med. 2020;133(5):621–6. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2019.10.028. PubMed

- Tan JW, Campbell DE. Insect allergy in children. J Paediatr Child Health. 2013;49(9):E381-7. doi:10.1111/jpc.12178. PubMed

On DermNet

- Allergies explained

- Anaphylaxis

- Angioedema

- Arthropod bites and stings

- Insect bites and stings

- Skin problems in farmers

- Urticaria

Other websites

- Insect Bites and Stings — Medline Plus

- Wasp Stings — Medscape Reference

- Hymenoptera Stings — Medscape Reference

- Insect sting allergy — Allergy New Zealand